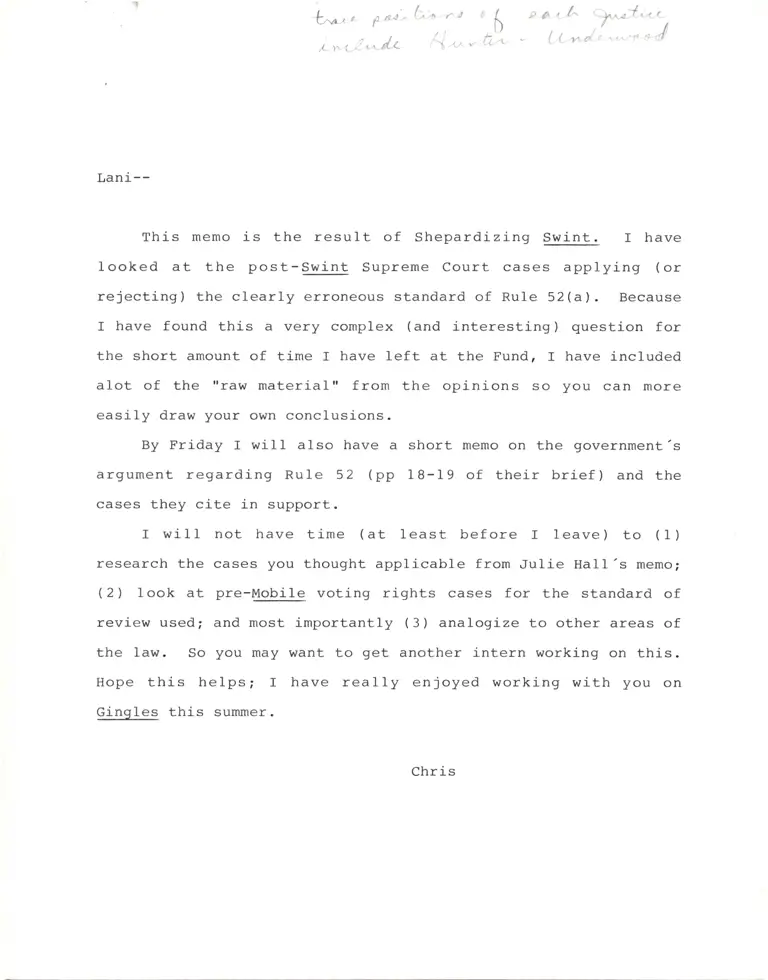

Memorandum from Chris to Guinier on FRCP Rule 52(a)

Working File

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Memorandum from Chris to Guinier on FRCP Rule 52(a), 1985. 32a489c7-dc92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/fa15496a-9e5f-4a4a-866c-f7865975cbe3/memorandum-from-chris-to-guinier-on-frcp-rule-52-a. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

t-,

,( ). (

f tar

,^ r/L

[^n r,t po I /^

rtd

^"j,,

/

I..,6

,Qr

Lani--

This memo j-s the result of Shepardrzing Swint. I have

looked at the post-Swint Supreme Court cases applying (or

rejecting) the clearly erroneous standard of Rule 52(a). Because

I have found this a very complex (and j-nterestirg) question for

the short amount of time I have left at the Fund, I have included

alot of the "raw material" from the opinions so you can more

easily draw your own conclusions.

By Friday I will also have a short memo on the government's

argument regarding Rule 52 (pp 18-I9 of their brief) and the

cases they cite in support.

I will not have time (at least before I leave) to (1)

research the cases you thought applj-cable from JuIie Hal1's memo;

(2) look at pre-@ voting rights cases for the standard of

review used; and most importantly (3) analogize to other areas of

the law. So you may want to get another intern working on this.

Hope this helps; I have really enjoyed working with you on

Ginqles this summer.

Chris

MEMO

To: Lani

From: Chris

Re: FRCP Rule 52(a)

Note: This memo picks up where Pam Karlan's memo left off.

For background on RuIe 52(a) see Karlan memo, especially pp l-ll,

1 9-40 .

A. Recent Supreme Court Cases Interpreting RuIe 52(a). (Cases in

chronological order. )

1. Pullman-standard v. Swint, 455 U.S. 273 (1982).

In Swint, Black employees sued their employer, alleging that

the seniority system maintained by the employer and the union was

discriminatory, in vioration of Title vrr. The District court

found that the system was not j-ntentionally discriminatory and

the Court of Appeals reversed. The Supreme Court granted cert on

the following question:

"Whether a court of appeals is bound by the 'cIearIy

erroneous' rule of FRCP 52 (a ) in reviewj-ng a district

court's findings of fact, arrived at after a lengthy trial,

as to the motivation of the parties who negiotiated a

whether if,e court below applied the

wrong legal criteria in determining the bona fides of the

seniority system.'. (456 U.S. 276, emphasis added)

Note that a violation of Titre vrr could only be found if

the seniority system was intentionally discriminatory; i.e.,

adopted because of its racially disparate impact. This is

obviously different than the "results" standard of Section 2 VRA

2

and Ginqles. However, the distrj-ct court in Swint found dis-

cri-minatory intent by Iooking at the "totality of circumstances"

and, in particular, four factors suggested by case law (see James

v. Stockham Valves a Fittinqs Co., 559 F2d 310 (1977)), which is

similar to the way discriminatory "results" are to determined

under amended s. 2 and according to the Senate Report (pp 28-30).

The Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Court of

Appeals. It explai-ned:

"Ru1e 52(a) broadly requires that findings of fact not

be set aside unless clearly erroneous. ft does not make

exceptions or purport to exclude certain categories of

factual findings from the obligation of a court of appeals

to accept a district court's findings unless clearly

erroneous. It does not divide facts into categories; in

particular, it does not divide findings of fact into those

that deal with 'ultimate' and those that deal with 'subsidi-

ary' facts.

The RuIe does not apply to conclusions of law. The

Court of Appea1s, therefore was quite right in saying that

if a district court's findings rest on an erroneous view of

the 1aw, they may be set asi-de on that basis. But here the

District Court was not faulted for misunderstanding or

applying an erroneous definition of intentional discrj-mina-

tion. It was reversed for arriving at what the Court of

Appeals thought was an erroneous finding as to whether the

differential impact of the seniority system reflected an

intent to discriminate on account of race. That question,

as we see it, is a pure question of fact, subject to RuIe

52(a)'s clearly-erroneous standard. It is not a question of

law and not a mixed question of law and fact.

The Court has previously noted the vexing nature of the

distinction between questions of fact and questions of

Iaw. (cites omitted) Rule 52(a) does not furnish particular

guidance with regard to distinguishing law from fact. Nor

do we yet know of any other rule or principle that will

unerringly distinguish a factual finding from a legaI

conclusion. For the reasons that follow, however, we have

little doubt about the factuar nature of s.703(h)'s require-

ment that a seniority system be free of any intent to

discriminate.

Treating issues of intent as factual matters for the

3

trier of fact is commonplace. . 'findings as to the

design, motive and intent with which men act' [are] pecul-

iarly factual issues for the trier of fact and therefore

subject to appellate review under Rule 52.' (quoting from

U.S. v. Yellow Cab Co., 338 U.S. 338 (1949)" (456 U.S. at

The Supreme Court, however, specifically differentiates this

"pure question of fact" of the motive or intent to discriminate

from findings of discri-minatory impact from which discriminatory

intent may legally be inferred that are questions of law or mixed

guestions of law and fact. "We do assert, however, that under

s.703(h) discriminatory intent is a finding of fact to be made

by the trial court; it is not a question of law and not a mixed

question of law and fact of the kind that in some cases may aIlow

an appellate court to review the facts to see if they satisfy

some legal concept of discriminatory intent./L9" 456 U.S. at 289

c n.19. Of course, what the Supreme Court is referring to here

is also not the s. 2 "resu1ts" standard; discriminatory results

are used to a11ow the Court to infer discriminatory "intent."

That type of presumption or judicial inference is more clearly a

"matter of law" in that it is an application of a legal standard

to facts found by a trial court. However, it must be noted that

the Court specifically reserves the question of the applicability

of RuIe 52(a) to "mixed questions of law and fact--i.e. questions

in which the historical facts are admitted or established, the

rule of Iaw undisputed, and the issue is whether the facts

satisfy the statutory standardr or to put it another way, whether

the rule of law as applied to the established facts j-s or is not

violated." 456 U.S. at 289,n. 19. It seems, therefore, that we

4

must argue that findings of discrlminatory "results" under s.2

are more like findings of intent then they are presumptions of

intent inferred from specific facts. ( "Discriminatory intent here

means actual motive; it is not a legal presumption to be drawn

form a factuar showing of something less than actuar motive.

Thus a court of appears may onry reverse a district court's

finding on discriminatory intent if it concrudes that the

finding is clearly erroneous under RuIe 52(a)." 456 U.S. at 2g}t

Final1y, the s.c. in swj-nt does away with the oId urtimate

fact/subsidiary fact distinction: "whether an ultimate fact or

not, discriminatory intent under s. 703(h) is a factual matter

subject to the clearly-erroneous standard of Rule 52(a)."

Blackmun and MarshalI di.ssented on the grounds that:

( 1 ) intent should not be required under Title VII; and

(2) the Court of Appeals met the'clearly erroneous'standard and

found legar errors with regard to the controlling lega1 princi-

p1es.

In general, the S.C. in Swint seems to be expanding the

situations to which Rule 52(a)'s clearly erroneous standard

applies--i.e. it applies to cases involving findings of discrimi-

natory intent. However, it does not settle the question of

whether a s.2 decision under the results standard would be

considered a question of Iaw or of fact, and leaves open a large

area of "mixed questions of law and fact" that may arso not be

subject to Rule 52(a)'s standard of review.

5

2. Inwood Laboratorj-es v fves Laboratories, 456 U.S. 844

(1982).

Inwood Labs involved the question of when "a manufacturer of

a generic drug . can be held vicariously liabIe for infringe-

ment of that tradmark by pharmacists who dispense the generic

drug." 456 U.S. at 846. The District Court concluded that no

trademark violation had occurred, but the Court of Appeals

reversed. The Supreme Court reversed the Court of Appeals.

The S.C. in Inwood Labs reaffirms that the Court of Appeals

in reviewing factual findings of the district court is bound by

Rule 52(a) and Swint. 456 U.S. at 855. The Court also reiter-

ates that if the trial court bases its decision upon a "mistaken

impression of applicable legaI principles" Rule 52(a) does not

apply. 456 U.S. at 855, n.15.

The Court concludes that the Appellate Court erred by

rejecting the District Court findings "simply because it would

have given more weight to evidence of mislabeling than did the

trial court . ." 456 U.S. at 856. "Determining the weight

and credibility of the evidence j-s the special province of the

trier of fact. Because the trial court's findings . were not

clearly erroneous, they should not have been disturbed." 456

U.S. at 856.

White and Marshall concurred in the

the Court of Appeals (and not the District

wrong legal standard for a trademark case.

Rehnquist concurred, but said that the

reversal stating that

Court) had applied the

case should have been

6

remanded to the Court of Appeals to determj-ne whether the factual

findings were clearly erroneous.

I do not think this case adds much to the analysis of the

application of Rule 52(a) in section 2 cases, but it is interest-

ing to note that even when a S. C. decision is unanimous, the

members have substantj-ve differences in their understandi-ngs of

the RuIe--i.e. the majority reverses because 52(a) was not

applied when the Court of Appeals reversed the Dj-strict Court on

the facts of the case; White and Marshall concur asserting

that the Appellate Court itself applied the wrong legal standard;

Rehnquist essentj-aIly agrees with White and Marshall but thinks

that under those circumstances, having corrected the Ct of

Appeals as to the legal rule to be applied, the case should be

remanded.

are a

3.

11

Citations in Shepard's to 456 U.S. 952t 955, 968, 969

cases remanded for consideration in light of Swint.

4. Roqers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982).

Rogers is the only one of

S.C. decisions that is a voting

these post-Swint-Rule-52(a)

rights case. It is not, of

standard of amended s. 2, butcourse, a case applying the results

instead applies the intent test of

ir).

Mobile (or something close to

The Distri-ct Court in Rogers found that the at-large system

of electj-ons in Burke County, GE was "maintained for invidious

7

purpos€s," i.e. to dilute the voting power of minorities in

violation of the 14th and 15th amendments. The Court of Appeals

affirmed the District Court, statj-ng that the district court

anticipated rygbf]-q in requiring proof of discriminatory purpose

and that its findings were not clearly erroneous.

The Supreme Court affirmed, concluding that the District

Court and Court of Appeals applied the correct legaI standard.

In addition, the Court stated:

We are also unconvinced that we should disturb the

District Court's finding that the at-large system j-n Burke

County was being maintained for the invidious purpose'of

diluting the voting strength of the black population. In

White v. Regester (cite) we stated that we were not inclined

to overturn the District Court's factual findings, 'repre-

senting as they do a blend of history and an intensely locaI

appraisal of the design and impact of the Bexar County

multimember district in the light of past and present

reality, political and otherwise.' (cites) Our recent

decision in Pullman-Standard v. Swint (cite;, emphasizes the

deference FRCP 52 requires reviewing courts to give a trial

court's findings of fact. 'Ru1e 52(a) broadly requires that

findings of fact not be set aside unless clearly erroneous.

It does not make exceptions or purport to exclude certain

categories of factual findings The Court held that

the issue of whether the differential impact of a seniority

system resulted from an intent to discriminate on racial

grounds'is a pure question of fact, subject to Rule 52(a)'s

clearly erroneous standard The Swint Court also

noted that j-ssues of intent are commonly treated as factual

matters . .We are of the view that the same clearly-

erroneous standard applies to the trj-aI court's finding in

this case that the at-Iarge system in Burke County is being

m

d ut's findings of fact to

be clearly erroneous, and this Court has frequently noted

its reluctance to disturb findings of fact concurred in by

two }ower courts We agree with the Court of Appeals

that on the record before us r none of the factual findings

are clearly erroneous." 458 U.S. at 622-23.

The Supreme Court then goes on to relate the District Court

findings which include evidence of bloc voting, absence of

8

minorities elected ( "the fact that none have ever been elected is

important evidence of purposeful exclusion" ), historical denial

of voting rights (e.9. due to use of poIl taxes), segregated

schools, unresponsiveness of elected officials to the needs of

the BIack community, depressed socio-economic status of minori-

ties. These numerous findings, similar (or identical) to those

required under amended s. 2 (and derived from the same case law)

led the District Court to conclude that the at-Iarge election

system was being maintained for invidious purposes. Affirming,

the S.C. stated:

"None of the District Court's findings underlying its

ultimate finding of intentional discrimination appears to us

to be clearly erroneous; and as we have saidr w€ decline to

overturn the essential finding of the District Court, agreed

to by the Court of Appeals, that the at-large system in

Burke County has been maintained for the purpose of denying

blacks equal access to the political processes in the

county. As in White v. Regester the District Court's

findings were 'sufficient to sustain Iits] judgment

and on this recordr w€ have no reason to disturb them. " 458

U. S. at 627 .

This opinion seems to me to be right in line with Swint.

Both are cases where the plaintiffs had to prove intentional

discrimination and in both cases the S.C. affirmed the District

Court's findings regarding discriminatory intent. Both of these

cases stregthen our argument that Rule 52(a)'s clearly erroneous

standard should apply to the decision in Ginqles in that the

district court is called on in aIl three cases to find similar

types of facts. However, these cases do not prevent the S.C. in

Gingles from ruling that RuIe 52(a) does not apply because the

"fact" found in Swint and Rogers was whether discriminatory

9

"intent" or "purpose" was present and not whether there hras a

discriminatory "result." In my opinion, discriminatory "results"

should all the more be a question of "fact" if discriminatory

"intent" is, but (see below) these cases are very unpredictable.

5. Brown v. Socj-aIist Workers '74 Campaiqn Committee, 459

u.s. 87 (1982).

Brown again raises the question of what is a question of

fact, what a question of Iaw and what a mixed question of 1aw and

fact. In Brown a three judqe district court held that an Ohio

campaign contribution and expense reporting law violated the 1st

amendment as applied to the SWP, "a minor political party which

historically has been the object of harassment by government

officials and private parties." 459 U.S. at 88. The S.C. affirm-

ed.

According to the S.C.:

"It]he District Court properly applied the Buckley Iv.-

Valeol test to the facts of this case. The District Court

found 'substantial evidence of both governmental and private

hostility toward and harassment of SWP members and support-

ers. '" 459 U. S. 99 .

This finding was based on evidence of specific incidents such as

threatening phone ca1Is, harassment of a party candidate, and FBI

surveillance. From this evidence,

"It]he District properly concluded that the evidence of

private and Government hostility toward the SWP and its

members establishesn. a reasonable probability that disclos-

ing the names of cdltributors and recipients wil l sub ject

them to threats, harassment, and reprisals."

"n. 19 After reviewing the evidence and the applicable law,

the District Court concluded: If]he totalitv of the cj-rcum-

10

stances establishes that, in Ohio, public disclosure that a

person is a member of or has made a contribution to the SWP

would create a reasonable probability that he or she would

be subjected to threats, harassment, or reprisals."

O'Connor, Rehnquist and Stevens concurred in part and dissented

in part. They concurred in the judgment with respect to the

disclosure of campaign contributors and that the "broad concerns"

of Bucklev v Va1eo applied to the disclosure of the recipients of

campaign expenditures, but dissented from the conclusion that the

SWP had sustained its burden of showing that "there is a reason-

able probability that disclosure of recipients of expenditures

will subject the recipients themselves or the SWP to threats,

harassment, or reprisals." 459 U.S. at 107.

opinion the dissenters state:

In Part II of their

"Turning to the evidence j-n this case, it is important to

remember that, even though proof requirements must be

flexible, Buckley, supra ., the minor party carries the

burden of production and persuasion to show that its First

Amendment interests outweigh the gove.rnmental interests.

Additionally, the application of the Bu*-ey standard to the

hi-storical evidence is most properlv characterized as a

mixed guestion of law and fact, for which we normally assess

the record independently to determine if it supports the

conclusion of unconstitutionality as applied.,/8"

"n.8 See Pullman-standard . The majority does not

clearly articulate the standard of review it is apptying.

By determining that the District Court 'properly concluded

the evidence established a reasonable probability of

harassment, ante at 100 . the majority seems to applv an

independent review standard. "

It is important to remember that the characterization of the

question in this case as a "mixed question of law and fact" and

therefore independently reviewable by an appellate court, is

by the dissent. However, the historical evidence relied on to

prove 'reasonable probability of harassment' seems similar to the

11

historical evidence of discrimination in s. 2 voting rights

cases. Also, in both cases intent is not requj-red to be proved.

Because this law/fact question seems quite arbitrary, the easiest

way to distinguish this caser or at least the dj-ssent's inter-

pretation of the case, is by noting that it is a constitutional-

1y-based lst amendment question--see Bose below. In addj-tion,

perhaps there is some difference between a test that looks at

whether discriminatory results have occurred in the past (fact

question) and one that looks to see whether there is a "reason-

able probabilj-ty" that harassment will occur j-n the future (legal

conclusion from the facts ) .

6. National Football Leagure v. North American Soccer

League, 459 U.S. L074, L076 (198?)

Denj-aI of cert; Rehnquist dissented from the denial and

cited Swint.

7. !!L44eeqEe State Board for Community Colleges v. Knight,

52 U.S.L.w. 4204 (Feb 21, 1984).

Knight j-nvolved the questi-on of whether a law restricting

the ability of public employees to "meet and confer" with their

public employers only through an exclusive representative

violates the lst and 14th amendment rights of employees not

members of the exclusive representative. A three judge court

found that speech and associational rights were deni-ed non-member

faculty. The S.C. reversed.

In his dissent, Stevens notes that the three judge court

t2

found "that under the statute 'the weight and significance of

individual speech interests have been consciously derogated j-n

favor of systematic, official expression These findings

may not be set aside unless clearly erroneous, see Inwood (cite),

Pullman (cite), and in any event are not challenged by appellants

or the Court." 52 U.S.L.W. at 4214-L5.

This case is an example of what is beginning to look like a

trend in the S.C.'s use of Rule 52(a): if j-nvokj-ng the clearly

erroneous standard will make a case come out the way the majority

desires, it is usedi if not, the majority will decide the case

and write the opinion without reference to it. A functj-onal ,

rather than theoretical, approach to the rule. In this case the

majority states :

"The District Court erred in holding that appellees had been

unconstitutionally denied an opportunity to participate in

their public employer's making of policy the scheme

violates no provision of the Constitution." 52 U.S.L.W. at

42t0.

This statement is vague: was it an error of law, the incorrect

application of a constitutional principle? or was it "clear

error" in their fact finding? And why was the case not remanded

if the lower court applied the wrong legaI standard? It seems

from the majority opinion that perhaps this is a mixed question

of fact and law --the application of a legal (constitutional)

standard to facts found by the trial court. Another possibility

is that the Court generally sees itself as having greater freedom

to review constitutional questions, and even the facts iD.

(:

I

-v

,

t-

(-

consti-tutional cases.

t3

8. Lvnch v. Donnellv, 52 U.S.L.W. 43L7 (March 5, 1984).

The S.C. uses (or ignores) RuIe 52(a) in Lvnch much as it

did in Knight. The issue in Lynch was "whether the Establishment

Clause of the First Amendment prohibits a municipality from

including a creche t ot Nativity Scene, in its annual Christmas

display. " 52 U.S.L.W. at 4318. In Lvnch, the District Court

found that the munici-pality-sponsored creche violated the

Establishment Clause, and the Court of Appeals affirmed that

decision. The S.C. reversed.

In the majority opinion the Chief Justice cites examples of

the religiousity of our society to explain why the Court does not

take "a rigid, absolutist view of the Establishment ClqrQy/e.', 52

U.S.L.W. at 4320. The Court states:

"The District Court inferred from the religious nature

of the creche that the City has no secular purpose for the

display. In so doing, it rejected the City's claim that its

reasons for including the creche are essentially the same as

its reasons for sponsoring the display as a who1e. The

District Court plainlv erred by focusing almost exclusively

on the creche. When viewed in the proper context of the

Christmas Holiday season, it is apparent thatr on this

record, there is insufficient evj-dence to establish IEEEE

inclusi-on of the creche is a purposef uI or surreptitious

effort to express some kind of subtle governmental advocacy

of a particular religious message The creche in the

display depicts the historical origins of this traditional

event long recognized as a National HoIiday. (cites omitted)

The narro$/ question is whether there is a- secular

purpose f or Pawtucket's display of the creche . fre E'IspIay

is sponsored by the City to celebrate the Holiday and to

depict the origins of that Holiday. These are legitimate

secular purposes. Ttft District Court's inference, drawn

from the religious nature of the creche, that the City has

no secular purpose was, on this record, clearly erroneous."-

52 U.S.L.w. at 4320-21.

Substance of this passage aside, the question is on what

I4

basis is the S.C. reversing the two lower courts? The S.C.

states that there was "insufficient evidence" and that the

"inference" drawn by the district court h,as clearly erroneous--

these seem to me to be issues of fact for which clearly erroneous

is the proper standard. (Were the findings "cIearly errone-

ous, or is it just that the District Court "rejected" the City's

claim and the S.C., if it were sitting as the trier of fact,

would have weighed the evidence differently? Even at its best,

clearly erroneous is a very subjective standard.) But the Court

also states that the district court focused on the h,rong ques-

tion--that it should have asked "whether there is a secular

purpose"--which to me seems like an application of the wrong

legal standard, a questj-on of law. (And if this is Sor shouldn't

the Court have remanded the case for consideration of the facts

by the Appellate Court according to the correct legal standard?

As I understand it, a remand is not necessary only if the facts

Iend themselves to only one interpretation, in which case the

appellate court can review the facts and a remand would be a

waste of judicial resources.) fn addition, this is a good

example of the Court ostensibly using the clearly erroneous rule

yet overturning the District Court findings when there seems to

me to be at least two equally plausible interpretations of the

facts. It is these sj-tuations, in particular, that the clearly

erroneous rule is supposed to protect the trial court's decisj-on,

even though had the appellate court sat as the trial court on the

case it would have decided differently.

15

In her concurrence, O'Connor asserts:

"r conclude that pawtucket's dispray of the creche doesnot have the effect of communicating endorsement of christi-anity.

The District court's qu.bsidiarv f indinqs on the ef f ecttest are consistent with tffihe court foundas facts that the creche has a religious content, tnaEwGffinot be seen as an insignificanl-part of the dispray,that its religious content is not neutralized by tfresetting, that the display is celebratory and not instruc-tional, and tf,.! the city aia not seek to counteract anypossible religious message. These findings do not implythat the creche communicates government approval of christi-anity. t!] The District courL arso foundl-however, that thegovernment was understood to prace its imprimatur on thereligious content of the creche. But whet-her a governmentactivity communicates endorsement of rerigion is not aquestion of simpre historical fact. alt4ou-qh. evidentiarvsubmi-ssions quffixe theuesti,on whethgr racial

commu,nicate an invidi aIstion to be ans icial interpreta-tr-on of soci-a acts. The District Court -s -EonET[ffii

concerning the effecf of pawtucket's display of its crechewas l_n error as a matter of law.,' 42 U.S.L.w. at 4324

so while the majority hold that the facts found by the trial

court were "crearly erroneousr', o'Connor believes that the

District Court found the facts correctly

legaI standard to them. Again, there is

but appl ied the hrrong

Iitt1e agreement even

within the s.c., and even between Justices who agree

as to what is a matter of fact and what of 1aw.

on a result,

Although I

believe o'Connor's approach the better of the two, r do not

understand her unsupported reference to "racial or sex-based

classifications Ithat] communicate an invidious message,' as

questions of 1aw. An "invidious message," r assume, wourd be

discriminatory intent, but the Court has clearly said that the

guestion of discriminatory intent is a question of fact (see

swint). rn addition, if the rest of the court accepts o,connor,s

16

vie$/ of the "judical interpretatj-on of social facts," it could

definitely hurt us in Ging1es. A new category of "social facts"

would give the S.C. free reign--since a "social fact" is somehow

different (and more like a rule of law) than a case-specific fact

and can be determined by the appellate court.

response the dissent 52 U.S.L.W. at 4331-33. )

( eut see in

In dissent, Brennan, Marshall, Blackmun and Stevens take

exception to both the majority's and O'Connor's view:

"In sum, considering the District Court's careful

findings of fact under the three-part analysis called for by

our prior cases, f have no difficulty concluding that

Pawtucket's display of the creche is unconstitutional. /Ll"

n.11 "The Court makes only a half-hearted attempt, see ante

. to grapple with the fact that Judge Pettine's detaj-Ied

findings may not be overturned unless they are shown to be

clearly erroneous. FRCP 52(a). See Pullman (cite). In my

view, petitioners have made no such showing in this case.

Justice O'Connor's concurring opinion properly accords

greater respect to the District Court's findings, but I am

at a loss to understand how the court's specific and well-

supported finding that the City was understood to have

placed its stamp of approval on the sectarian content of the

creche can, in the face of the Lemon test, be dismissed as

simply an "error as a matter of law. "

9. Bose Corportation v Consumers Union of United States, 80

LEd 2d 502 (1984).

In Bose, the court considered the question:

"Does Rule 52(a) of the FRCP prescribe the standard to be

applied by the Court of Appeals in its review of a District

Court's determination that a false statement was made with

the kind of 'actual malice' described in NYT v Sullivan?"-

(cite omitted) B0 LEd 2d at 508

The case concerned "product disparagement" and

found for the plaintiff. The Court of Appeals

the District Court

reversed, agreeing

"it stated that it 'must perform a de novo review, independ-

ently examining the record to ensure that the district court

has applied properly the governing constitutional 1aw and

that the plaintiff has indeed satisfied its burden of

proof.'" 80 LEd 2d at 5I1.

Based on its o$/n review, the Court of Appeals did not find

evidence that the statement was published "with knowledge that it

was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or

not. "

Since the S.C. has stated that "intent" is a question of

fact to which Rule 52(a) is applicable, one

with the district court that

aging and false, but on its

"actua1 malice." The Court

standard did not apply to

determination:

"malice" would also be a fact question. The

n.15 at 515 ("Indeed, in Herbert v Lando,

(1979 ) we referred in passing to actual ma

fact. " ) In addition, this is a rather trivial

could have been overturned even under the

standard.

But according to Stevens,

"faithful to both Rule 52(a) and

l7

the comment in questJ-on was dispar-

own review of the record finding no

of Appeals held that Rule 52(a)'s

its review of the "actual malice"

might guess that

S. C. notes this i-n

441 u.s. 153, 170

lice as "ultimate

case that probably

clearly erroneous

the appellate court must be

the rule of independent review

applied in N.Y.T. v Su1livan." 80 LEd2d at 5I5. He states that

the conflict between the two rules is "more apparent than real,'

because to determine if something is clearly erroneous under RuIe

52(a) a judge must looke at--or review--the entire record.

18

80 LEd 2d at 516. Conversely, the independent review rule aIlows

the trial judge's opportunity to observe demeanor "to be given

its due." B0 LEd 2d at 515. This attempt at reconciliation seems

incorrect: The standard of review under 52(a) is "clearly

erroneousr" while the standard of review under "the constitution-

aIly-based rule of independent review" is "de novo. " In additJ-on,

Rule 52(a) applies to facts while a rule described as "constitu-

tionally based" seems more a rule of Iaw.

The next few paragraphs of Stevens' opj-nion (at 516-517) is

dicta on Rule 52, fact finding, and the difference between "live

cases" and "paper cases.r' He states, "The same clearly erroneous

standard applies to findings based on documentary evidence as to

those based entirely on oral testj-mony . but the presumption

has lesser force in the former situation than in the latter." In

n. 16 he quotes from Baumgarten v U.S., 322 U.S. 665 (1944)z

'The conclusiveness of a 'finding of fact' depends on the

nature of the materials on which the finding is based

Thus, the conclusion that may appropriately be drawn

from the whole mass of evidence is not always the ascer-

tainment of the kind of 'fact' that precludes consideration

by this Court. (cites) Particularlv is this so where a

decision here for revi"

whole nature of one Government and the duties and immunities

of citizenship.'

Again, much of this seems incorrect--the idea that the clear

erroneous standard is a presumption of varying strength, etc.

but it does give the Court a lot of leeway in their interpreta-

tion and application of RuIe 52. Stevens goes on to state that

the difference between the clearly erroneous rule and the

independent review rule is that "the rule of independent review

1y

19

assigns to judges a constitutional responsibilitv that cannot be

delegated to the trier of fact ." 80 LEd 2d at 516. To

distinguish Ginqles from Bose--GingIes is a statutory case,

j-nvolving no constitutional question and so not inviting a

constitutionally based standard of review. GeneraIIy, the Court

has allowed greater appellate review of constitutionally based

cases (see Karlan memo pp ) tn his opinion, Stevens emphasizes

the special role of the Court in consitutional and, in partic-

ular, 1st amendment cases:

"The requirement of independent appellate revi_ew

reiterated in NYT v Sullivan is a rule of federal constitu-

tional law It reflects a deeply held conviction thatjudges--and particularly members of this Court--must

exercise such review in order to preserve the precious

liberties established and ordained by the Constitution

" 80 LEd 2d at 523.

Arguably, this reasoning is not at all- applicable to s.2 cases

and Ginqles; however, there may be some risk that the Court will

talk about voting rights generallv as a Constitutional right and

therefore subject to greater review.

Final1y, Stevens states many of the well-worn principtes of

Rule 52(a) concerning the difficulty of distinguishing fact from

law. 80 LEd 2d at 517. In n.17 he states:

"A finding of fact in some cases is inseparable from

the principles through which it was deduced. At some point,

the reasoning by which a fact is'found'crosses the line

between application of those ordinary principles of logic

and common experc which are ordinarilv entrusted to the

flnaeffie realm of

@tmustexerciseitsownindependentjudgment.

Where the line is drawn varies according to the nature of

the substantive Iaw at issue. Regarding certain Iargelv

factual _questions in some areas of the 1aw, the stakeEl-fn

terms of impact on future cases and future conduct-:aie Eoo

great to entrust them finally to the judgment of the trier

20

of fact. "

I don't know what Stevens was thinking about here but I hope it

wasn't Voting Rights. This footnote is so vague I don't exactly

know how to rebut it, but again it opens a door to the Court that

they may or may not choose to walk through. Again, discrimina-

tory "results" seems a factual, not a lega1 question--but perhaps

not one for which principles of ordinary "logic and common

experience" are sufficient.

In dissent, Rehnquist, O'Connor and, separately, White note

that "in the interest of protecti-ng the lst amendment, the Court

rejects the 'clearly erroneous' standard of review mandated by

FRCP 52(a) in favor of a'de novo'standard of review for the

'constitutional facts' surrounding the 'actual malice' determina-

facts" heretion. 80 LEd 2d at 526. (Note that "constitutional

are treated somewhat similarly to "social facts" in

dissent states:

Lvnch). The

"in my view the problem results fromtthe Court's

attempt to treat what is here, and in other contexts always

has been, a pure question of factr ds something more than a

fact--a so-caIled 'constitutional fact.' B0 LEd 2d,at 527.

The dissent believes that malice is a determination regarding the

state of mind of a particular person at a particular time--a

historical fact--and appropriate for determination by the trj-aI

court:

"I continue to adhere to the view expressed in Pullman-

Standard v Swint (cite) that RuIe 52(a) 'does not make exceptions

or purport to exclude certain categories of factual findings from

the obligation of a court of appeals to accept a district court's

findings unless clearly erroneous.' There is no reason to depart

from that rule here, and I would therefore reverse and remand

this case to the Court of Appeals so that it may apply the

2L

'clearly erroneous' standard of review to the factual findings of

the Di-strict Court. "

10. Anderson v Cj-tv of Bessemer, 84 LEd 2d 518 (1985).

The Court in Anderson returns to the use of the clearly

erroneous as in Swint; Iike Swj-nt, Anderson involved a finding of

discriminatory intent under Title VII. The District Court found

that the petitioner had met her burden of establishing that she

had been denied the position of Recreation Director because of

her sex. The Fourth Circuit reversed concluding that three of

the District Court's crucial findings were clearly erroneous and

that the District Court erred in finding sex discrimination. The

S.C. reversed the Court of Appea1s.

The question in this case is not whether Rule 52(a) applies-

-clearly it does due to the precedent of Swint--but whether the

Court of Appeals applied the clearly erroneous standard correct-

Iy. 84 LEd 2d at 528 ( "Because a finding of intentional discrim-

ination is a finding of fact . . " ) the Court begins by

citing the Gypsum definition of when a fact finding is clearly

erroneous (see Karlan memo). In addition, it states:

"This standard plainly does not entitle a reviewing court to

reverse the finding of the trier of fact simply because it

is convinced that it would have decided the case different-

ly. The reviewing court oversteps the bounds of its duty

under Rule 52 if it undertakes to duplicate the role of the

lower court. 'In applying the clearly erroneous standard to

the findings of a district court sitting without a jury,

appellate courts must constantly have in mind that their

function is not to decided factual issues de novo.' Zenith

Radio Corp v Hazeltime Research, Inc. 395 U.S. 100 (1969).

If the district court's account of the evidence is plausible

in light of the record viewed in its entirety, the court of

appeals may not reverse it even though convinced that had it

22

been sitting as the trier of fact, it would have weighed the

evidence differently. When there are two permissj-ble views

of the evidence, the factfinder's choice between them cannot

be clearly erroneous. U.S. v Ye1low Cab Co 338 U.S.338

(1949) see also Inwood Lab v Ives Lab 456 U.S. 844 (1982).

Although the context of this language is a case where there was

no question that Rule 52(a) applied and so it is not directly

applicable to Gingles where we are arguing that RuIe 52(a) should

apply, the reasons cited seem equally true for the argument

that RuIe 52(a) should apply as to how to apply it once it does.

The Court goes oDr in direct contradiction to Bose, to state

that trial court findings are equally protected whether based on

"papertt or ttlivett evidence:

"The rationale for deference to the original finder of

fact is not limited to the superiority of the trial judge's

position to make determinations of credibility. The trialjudge's major role is the determination of fact, and with

experience in fulfilling that role comes expertise.

Duplj-cation of the trial judge's ef f orts in the Court of

Appeals would likeIy contribute only negligibly to the

accuracy of fact determination at a high cost in diversj-on

of resources. In additionr the parties to a case on appeal

have already been forced to concentrate their energies and

resources on persuading the trial judge that their account

of the facts is the correct one; requiring them to persuade

three more judges at the appellate level is requiring too

much. As the Court has stated in a different context, the

trial on the merits should be'the'main event' . . .rather

than a 'tryout on the road. " Waj-nwright v Sykes 433 U.S. 72

(1977). For these reasons, revi-ew of factual findinqs under

the clearlv-erroneous standard--with its deference to the

trier of fact--is the ru1e, not the exception.

Again, this discussion i-s helpful and applies equally to the

question of why the facts found by the trial judge in Gingles

should be regarded just as that--facts-- and not as "sociaI" or

"constitutional" facts to be reviewed under another standard.

(tn addition, it would be ironic if findings of discriminatory

23

intent--which are more difficurt to prove and more likery just

unknowable (see regislative history)--were Bore. protected than

f indings of di-scrimi-natory results, since the results standard

was designed to be more a fact-based inquiry, and easier to

establish than intent. )

The S.C. concludes that the 4th Circuit "improperly conduct-

ed what amounted to a de novo weighing of the evidence in the

record" rather than just determining if the District Court's view

was plaus j-ble. "The question we must answer , however , i s not

whether the 4th Circuit's interpretation of the facts was clearly

erroneous, but whether the District Court's finding was clearly

erroneous." B4 LEd 2d at 530. FinaIly, the S.C. disclaims any

superior knowledge of what was in the mj-nds of the defendants:

"Even the tri-aI judge, who has heard the witnesses directly

and who is more closely in touch than the appeals court with

the milieu out of which the controversy before him arises,

cannot always be confident that he'knows'what happened.

Often, he can only determine whether the plaintiff has

succeeded inpresenting an accountof the facts that is more

Iikely to be true than not. Our task--and the task of

appellate tribunals qenerally--is more limited stiIl: we

must determine whether the trial iudqe's conclusions are

clearly erroneous." 84 LEd 2d at 533

Some General Conclusions

The strongest argument in favor of applying RuIe

52(a)'s clearly erroneous standard in s.2 VRA cases is Rogers.

Rogers is a voti-ng rights case, though one using an intent

standard, and the proof required for Rogers is very similar to

(though slightly less demanding, accordj-ng to the legislative

history) thrat presented in Gingles. Also, Rogers emphasizes the

B.

24

loca1 nature of the fact finding in voting rights cases ( see

above p.7l and relies on Swint. [uote that if this approach is

taken, someone should ]ook at the standard of review in other

votJ-ng rights cases, something I did not have time to do.I

SimiIarIy, Swint and Anderson are discrimination cases

where the clearly erroneous standard has been used. That these

cases h/ere "intent" cases while Gingles is a "results" case

should be a strength and not a weakness, since discriminatory

results are somehow more "factual" or knowable than intent. On

the other hand, I think the S.C. has been very inconsistent in

its application of the clearly erroneous standard, and without an

exact precedent it is hard to predict what they will hold.

Brown, Knight, Lynch, and Bose can be distinguished as

constitutionally based cases, while Gingles is a statutory case.

Ittote that this assumes that the Court wilI not simply character-

ize "voting rights" as a constitutionally-protected right,

despi-te the statutory c1aim. Perhaps someone knows the answer to

this or can do some research on the question. ]

Finally, it seems to me that the Court uses the fact/Law

distinction in a very arbitrary way depending on how they wish

the case to come out. This j-s especially true when they talk

about "constitutional facts" or "social facts" which can be

reviewed by appellate courts. Perhaps the best arguments to

counter this tendency are the judicial economy arguments from,

in particular, Anderson.

<-<:,

I

f

L.i .,