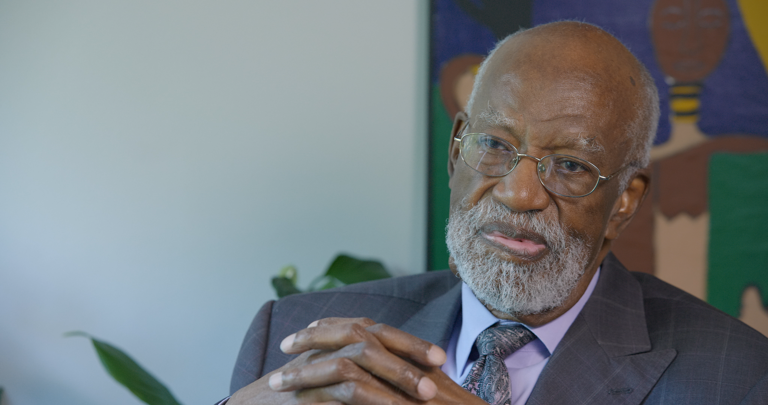

James Ferguson: Advocating for Civil Rights Inside and Outside of the Courtroom

In May 1954, eighth grader James Ferguson was helping his teacher run errands in Asheville, North Carolina, when he heard the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision announced on her car radio. The landmark case, which was argued by Thurgood Marshall and his team at the Legal Defense Fund (LDF), declared school segregation and allegedly “separate but equal” schools unconstitutional. Ferguson had expected to go to ninth grade at Stephens-Lee, the all-Black high school in segregated West Asheville. Now, he thought he could instead attend Lee Edwards, an all-white high school in Asheville that had a better-looking building, a much larger campus, and newer books. In a 2023 interview for the Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project, Ferguson recalled his excitement as he turned to his teacher, Annabelle Logan.

“Well, Ms. Logan, that means I can go to Lee Edwards High School next year,” he said at the time. His teacher nodded in agreement. “But I know now,” Ferguson reflected in 2023, “that within herself, she knew that was not likely to happen.”

As Ferguson began ninth grade at Stephens-Lee High School, he waited for the announcement that he could soon attend the white high school instead. But it did not come. It did not come during his sophomore year either, or during his junior or senior year.

In 1970, 16 years after the Brown decision, Ferguson—now partner in the North Carolina civil rights law firm Chambers, Stein, Ferguson, & Lanning, P.A.—would lead a lawsuit that held Asheville City Schools accountable for its failure to implement a true desegregation plan. His personal experiences fighting against segregation as a teenager informed his future legal path, one that took him to Columbia Law School and to a private practice that worked closely with LDF.

Growing Up in the South

“Everything about Asheville was determined, defined, delineated by race in one way or another,” Ferguson said of his childhood home. His father worked a variety of blue-collar jobs, and his mother stayed at home with their seven children before later working as a maid for a white household. As the youngest child, James was unaware of his parents’ struggles with racism or supporting their family on modest incomes. “There was a lot of love and joy in my family,” he reflected.

As he played outside with other Black kids in the neighborhood, he did not realize “how utterly deprived” Black children were of the resources available to white kids. “You made do, as I used to say, with what you had, and that’s what we did.”

Ferguson began noticing that schools and parks for white children had nicer playgrounds than those for Black children as he moved through elementary school. However, he sensed that he should not complain or ask about these differences.

“Black people knew as a matter of survival that you didn’t make a cause of the inequality that was everywhere.”

Observing the behaviors of his parents and other Black adults, Ferguson realized that their shared goal was to maintain peace in their personal lives and in the Black community, despite the pervasive racism that impacted every aspect of their lives.

“As a Black young person growing up, it was communicated to us that there were certain things that we were prohibited from doing because we were Black, and that only whites did,” Ferguson said. “Nobody taught you a class on what you could do or not do. You picked it up and you knew that this became the custom, and that custom was every bit as clear as law because that’s the way the whole community operates.”

A Young Activist

Even so, many Black adults supported Ferguson when he began organizing civil rights protests as a teenager. He discovered that, beneath their seeming reluctance to challenge the established racial order, many people had an untapped desire to push for justice.

Persistent school segregation even in the wake of Brown sparked his activism. After the Supreme Court issued the Brown ruling on May 17, 1954, several states immediately filed lawsuits asking for exemptions. The Court unanimously ruled against them on May 31, 1955, in the case known as Brown II. In the decision, Chief Justice Earl Warren instructed localities to desegregate public schools “with all deliberate speed” but charged school boards—the very entities that had rigidly maintained school segregation—with the responsibility of forming and executing plans to do so. Because the Court did not order a specific deadline for school integration, states, localities, and school boards used every available means to avoid desegregating schools. Their tactics were effective.

The History of Massive Resistance to School Desegregation

After the Supreme Court declared “separate but equal” public schools unconstitutional in the 1954 landmark ruling Brown v. Board of Education, Senator Harry Flood Byrd of Virginia responded with a call to action: “If we can organize the Southern States for massive resistance to this order, I think that, in time, the rest of the country will realize that racial integration is not going to be accepted in the South.” Segregationists across the South adhered to this message, and Massive Resistance emerged as the main strategy to defy the Supreme Court and preserve white supremacy.

Massive Resistance refers to a constellation of state laws and policies executed to resist desegregation. Byrd’s “Southern Manifesto on Integration,” signed by 96 members of Congress, maligned Brown as an unconstitutional overreach of federal power. The signatories to the manifesto pledged “to use all lawful means to bring about a reversal of this [Brown] decision ... and to prevent the use of force in its implementation.” States took extreme measures to carry out this plan.

In Byrd’s home state of Virginia, for instance, Governor Thomas B. Stanley authorized a plan that cut funding from any school district that attempted to integrate, resulting in the closure of nine schools. In 1955, North Carolina became the first state to pass a “pupil placement law,” which gave local school districts the authority to assign students to schools in a discriminatory fashion, and other states soon followed suit. White families mobilized to establish all-white private schools, while state legislatures authorized tuition grants for parents who opposed integration.

Marian Wright Edelman, an attorney at the Legal Defense Fund, characterized Massive Resistance and these associated policies as “legalistic horseplay to keep Negro children out of white schools.” She and other civil rights attorneys brought lawsuits challenging Massive Resistance on constitutional grounds, while Black students bravely fought against it by enrolling in previously segregated schools. Because Massive Resistance was a coordinated, multidisciplinary endeavor, it took an organized coalition of attorneys, students, and activists to defeat it.

“And it so happened that nothing changed in Asheville,” Ferguson said. “Nothing changed. Not a single school changed from the eighth grade until I finished high school.”

The school board’s inaction turned him and his friends into activists. In junior high and early high school, Ferguson participated in the Greater Asheville Intergroup Youth Association, an organization that brought together young teenagers from local Black and white schools. The experience taught him how to find commonalities with people from different backgrounds, as did his affiliation with The National Conference of Christians and Jews. Both of these groups, however, had to meet outside of Asheville because they could not find a place inside the city limits that allowed integrated meetings.

Driven by a desire to integrate spaces, Ferguson and his like-minded peers formed the Asheville Student Committee on Racial Equality (ASCORE), a student chapter of the national CORE—one of the most prominent organizations during the Civil Rights Movement. In ASCORE, Ferguson and his colleagues studied and discussed the nonviolent protest strategies they saw in the news. They noted that college student activists often organized sit-ins, but Asheville did not have a college. If they wanted to desegregate lunch counters, the ASCORE teenagers realized, they would need to organize their own sit-ins.

Ferguson said the adults in his life encouraged ASCORE to meet with Ruben Dailey and Harold Epps, two local Black lawyers. The teenagers assumed the lawyers would lecture them against certain types of protests in order to maintain peace and avoid legal trouble. They were wrong: The lawyers offered their full support. Ferguson recalled the lawyers telling him and his friends, “You all do what you’re going to do, and if you get into legal trouble, you can call on us and we’ll be there for you and we’ll help you. And we’re not going to charge you anything.”

Empowered by this encouragement, ASCORE reached out to the white adults who owned stores and managed lunch counters in town. Their careful consideration of other nonviolent protests had taught them to engage before creating a confrontation. “You first identify the problem. Then you meet with those who might be able to resolve the problem,” Ferguson said. “And then ultimately, if you weren’t successful in getting the problem addressed, you would do direct action with sit-ins or demonstrations or whatever you needed to do.”

The teenagers’ preparation and strategy worked. Owners and management at three Asheville department stores—S. H. Kress & Co., Newberry’s, and Woolworth’s—agreed to desegregate their lunch counters, so there was no need for a sit-in. ASCORE members realized that because Asheville, with its picturesque mountain scenery, was a tourist destination, the white community did not want civil rights protests to draw publicity that might scare away visitors. Working methodically with other white store owners, Ferguson and his ASCORE peers helped to eventually desegregate several more lunch counters and public facilities. Their activism also led to the hiring of Black clerks and other staff at area stores.

Despite these successes, ASCORE’s work did not expedite school integration. Ferguson and his classmates met with the white superintendent and the chair of the school board to ask when Asheville City Schools would become desegregated, but they walked away “disappointed to find that there were not going to be any real changes.” The local white establishment drew a line at the schoolhouse door. However, ASCORE did manage to organize so many student activists that, threatened with walkouts and sit-ins, the school board decided to address some of their concerns. But instead of integrating the student bodies, the school board reinforced segregation by building a new Black high school, a tactic adopted by a number of Southern school districts. It was better than the old building, Ferguson reflected, but not “anywhere close to comparable” with the all-white Lee Edwards High, which resembled a college campus. Separate was never equal.

“Looking back, I realized they were willing to do anything except desegregate the schools,” Ferguson said.

Pursuing the Law

Upon his high school graduation, Ferguson knew that he wanted to be a lawyer like Dailey and Epps, the local Black attorneys who had encouraged his activism. He went to North Carolina Central University in Durham, a historically Black college, where he pursued a double major in history and English and served as the president of the Student Government Association. Ferguson, a stellar undergraduate, found a mentor in Professor Caulbert Jones of the History Department. Jones advised him on his law school search and also encouraged Ferguson to follow the example set by another of his star students, an alumnus named Julius Chambers who would later become the third Director-Counsel of LDF.

In 1964, Ferguson entered Columbia Law School as one of its only Black students. While many of his classmates aspired to a job at a prestigious corporate law firm, he remained committed to returning to North Carolina so he could “do something to help the Black community.” He said, “I knew from the beginning, from the day I walked in, applied to that law school, that my purpose was to go back South.”

He learned that LDF, which was based in New York City, helped Black lawyers like him set up civil rights practices in the South. During the spring of his third year in law school, he visited the LDF offices in Columbus Circle hoping to learn about available opportunities. There he met LDF Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg, who introduced him to a young intern named Julius Chambers. Ferguson was shocked to meet the very student who had earned Professor Jones’ praise. “I mean, it was like the gates of heaven opening up,” Ferguson reflected.

When Chambers learned that Ferguson wanted to return to the South to practice civil rights law, he saw an opportunity for collaboration. He invited Ferguson to spend spring break with him and his wife, Vivian, at their home in Charlotte, North Carolina. At the end of that week, Chambers asked Ferguson to join him in his law practice. The small walk-up office had a space called “the library” furnished with only a table and two chairs. A young white lawyer named Adam Stein took one chair, and Ferguson took the other. Together, they learned on the job how to practice civil rights law in addition to addressing a variety of other legal issues Black people were facing. People would come to them because they knew “Mr. Chambers was going to help them in one way or another,” Ferguson reflected, calling it “a people’s law practice.” He summarized their mission: “If you had a problem, our job was to find a way to help you. And we tried to do that.”

Ferguson drew upon his personal experiences to shape his view of the law. One of his most salient legal lessons came during his sophomore year at Stephens-Lee High School in Asheville, when nine of his Black friends were charged with raping a white woman after visiting an all-white park one evening. The young men had invited Ferguson to go with them that night, but he had gone to a school dance instead. Although the accused teenagers denied the charges, each entered a guilty plea because a rape conviction carried the death penalty, and they knew they would likely face an all-white jury. By pleading guilty, Ferguson learned, his classmates could avoid the death penalty and instead get a life imprisonment sentence with a potential for parole in 20 years. The experience taught him two valuable lessons: The first was that not every person who pleads guilty or serves time in prison is actually guilty; and the second was that, since he could easily have gone with the group that night and faced a conviction himself, an accused person is not “some evil, bad person who deserved to be in prison, but they were people who had unfortunate turns of events.” Ferguson applied this compassion and understanding of human behavior to his law practice.

“We have to be careful and reserved in our judgment of people,” Ferguson said. “You can’t judge people just by what you see in the moment, but you have to understand who they are, how they got to where they were.”

An Integrated Law Firm Fighting for Integrated Schools

After several months in Charlotte, Ferguson and Stein joined Chambers and a local white lawyer named Jim Lanning to create the first racially integrated law firm in North Carolina. Often working as local counsel with LDF, Chambers, Stein, Ferguson, & Lanning represented clients in both criminal cases and civil rights lawsuits. Some of the young firm’s most controversial and impactful work centered on school desegregation.

In the years following Brown v. Board of Education, LDF sued hundreds of school districts across the country to implement desegregation in the face of massive local resistance by white politicians and civic leaders. Change slowly began to happen toward the end of the 1960s, when the Supreme Court decided in the 1968 case Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, Virginia that “freedom of choice” school plans—where all students could choose which school they wanted to attend—failed to adequately dismantle segregation. Siding with LDF, the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Green pushed school districts to adopt plans that more aggressively identified and implemented effective methods of integration, such as busing.

Chambers and his partners used this decision to their advantage in subsequent desegregation cases. In 1970, working with Dailey (one of the Black Asheville attorneys who had encouraged his high school activism), Ferguson led B. Lee Allen, et al. v. Asheville City Board of Education, a lawsuit that held the district accountable for the ways in which it assigned and bused K-12 students to integrated schools. That same year, Chambers argued the landmark case Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education before the U.S. Supreme Court. Chambers asserted that federal courts were constitutionally authorized to oversee and produce remedies for state-imposed segregation, and that the Supreme Court should uphold busing programs as a way of accelerating integration in public schools. Critics of busing argued that the practice would encourage interracial violence and was unconstitutional because it put social and economic burdens on students who had to travel long distances between their homes and their new schools.

“The Office Is on Fire”

As the country waited for the Supreme Court’s verdict in Swann, frustration over the struggle for equity in education intensified, and protests turned violent. At around 4:30 a.m. on February 4, 1971, two months before the Court announced its decision, arsonists firebombed the Charlotte offices of Chambers, Stein, Ferguson, & Lanning. For Chambers, this was the latest in a line of targeted attacks: His home and car had each been firebombed in 1965, and his father’s auto repair garage had been bombed twice. Nobody was killed, but Chambers’ wife, Vivian, worried for her family’s safety. At the time of the Charlotte office attack, Chambers was out of town working on another case. Ferguson heard about the office fire when Vivian called him early in the morning.

“Fergie, Fergie, the office is on fire!” Ferguson recalled her crying.

She later told a reporter that the arson attack triggered memories “of the night they bombed our house.” She shared that someone had been repeatedly crank-calling her house, breathing heavily into the phone without talking. “I know it’s the person who’s setting the fires,” she said.

Ferguson immediately drove to the site, where he saw flames shooting out of the doors and windows of the office building, a two-story, 14-room converted house. The Charlotte Observer reported that it took 50 firefighters with seven trucks about an hour to bring the blaze under control. Piles of legal records were destroyed. Although a fire official assured Ferguson that authorities would find out who set the fire, he had still not received an answer decades later.

The arson attack rattled but also motivated each of the partners at Chambers, Stein, Ferguson, & Lanning.

“We all redoubled the work that we were doing and redoubled our determination to continue to see this work through at that time,” Ferguson said. “Not a single one of us ever for a second entertained the thought that this was it. … I think we all knew that no matter what the outcome of that fire was going to be, the fire within us could not be extinguished, and we would continue to follow that fire until we had done all that we could possibly do to bring about the society that we wanted to see at that time.”

They received some good news two months later, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its Swann decision on April 20, 1971. In a unanimous decision, the Court upheld busing programs as constitutional and found that federal district courts could oversee desegregation plans in school districts that had violated previous mandates to integrate—a decision that expedited integration efforts throughout the South.

The firm also worked on other important civil rights cases: On February 6, 1971, days after the office firebombing, arsonists set a white-owned convenience store on fire in a predominantly Black neighborhood in Wilmington, North Carolina. Racial tensions over school segregation there had led to a riot and the deployment of the National Guard. Police later arrested 10 people who became known as “the Wilmington 10”—eight Black high school students, a Black minister, and a white social worker—for arson and conspiracy. Ferguson served as their defense attorney. After a jury convicted them, he led their multiyear appeals process, which drew international attention for its charges of prosecutorial misconduct. Amnesty International declared the Wilmington 10 “prisoners of conscience,” and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit overturned the convictions in 1980 on the grounds that legal errors and prosecutorial misconduct had denied them their constitutional right to due process. Decades later, Governor Beverly Perdue pardoned them in 2012.

The firm was also local counsel in the landmark 1986 Supreme Court case Thornburg v. Gingles, which is one of the most consequential cases interpreting the Voting Rights Act. This North Carolina case upheld the 1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act and set the standards by which vote dilution claims brought under Section Two are litigated, marking an important civil rights victory.

The Work Continues

Unfortunately, civil rights progress has not been linear. For a time, Charlotte and Asheville had more integrated schools, and Black students could hope to achieve an equal public education to white students. It did not take long, however, for desegregation efforts to break down. Ferguson said that integration “lasted as long as the white power structure and the white community allowed it to last. But it came to an end in the way that things come to an end without having an end declared.” Resistance to school integration has resulted in persistently racially homogenous schools, and “all of the litigation in the world has not changed that.”

As of 2024, Ferguson continued to practice law in Charlotte, at the firm he helped found decades ago. A distinguished trial lawyer, law professor, and member of The Inner Circle of Advocates, he has chaired multiple legal organizations and co-founded South Africa’s first Trial Advocacy Program. In addition to handling criminal and civil rights cases, he has concentrated on personal injury litigation. Ferguson has served as a mentor to countless young civil rights lawyers across the country.

Looking back on six decades of his legal career, Ferguson remarked that in some ways, America has made progress with civil rights, but in others, it has stepped into the past.

“We like to believe, in spite of some things we see today, that we’re still moving in that direction to bring about what the Legal Defense Fund has been about for decades,” he said. “We see progress and then we see retrogression in whatever that progress has been, but we still come back and find ourselves pushing towards that society, which is going to come one day, where every citizen is judged by the content of his or her character and not by the content of his or her color.”