Melvyn Leventhal: A Dedicated Student of Education Equity

Melvyn Leventhal at work. Image taken from the LDF archival records.

When he was 7 years old, Melvyn Leventhal accompanied his mother to a movie theater in his hometown of Brooklyn, New York, to watch a baseball biopic that validated the person he thought he was and the man he hoped to become. "The Jackie Robinson Story," starring the Brooklyn Dodgers hero as himself, chronicled the racism and prejudices Robinson endured during his pioneering career as a college athlete and the first Black ballplayer in Major League Baseball. The movie struck a nerve in young Leventhal, who had personal experiences with anti-Semitism.

"I immediately felt empathy, and I cried during the movie," Leventhal explained during a 2023 interview for the Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project.

"I think it was just a very important moment, and I believe that what I felt was something innate. I don’t think that it emerged from the film—I think it was there before the film. But it showed me who I am, something that was important to me, and it remained an image in my life forever."

Leventhal said he considers the inspirational movie, released in 1950 to critical acclaim, as "part of the bedrock of the Civil Rights Movement" and "one of the building blocks" that helped make a difference in race relations.

Another formative experience happened when Leventhal was 9, as he went to court several times during his parents' bitter divorce proceedings. The judge's authoritative manner made a significant impression on young Leventhal and sparked his ambition to become a lawyer.

"I think I always wanted to go to law school, and I also wanted to be a leader," he said. In the midst of the divorce, "in a cab ride home from one of the court appearances, I said to my mother, 'I know what I want to be: I want to be a judge because he tells everyone what to do,'" Leventhal recalled with laughter.

These experiences pointed Leventhal toward a future of barrier-breaking personal and professional relationships that would leave indelible marks in the fight for racial justice in the United States.

Mississippi Yearning

In 1963, a group of law students inspired by the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom founded the Law Students Civil Rights Research Council (LSCRRC) to promote discussion of civil rights and provide research for civil liberties cases. The nonpartisan organization set up chapters at law schools around the country, encouraging students to use their legal, organizational, and leadership skills to promote economic, racial, ethnic, and gender equality. The LSCRRC offered summer internships and partnered with organizations such as the Legal Defense Fund (LDF) and the American Civil Liberties Union to provide students with real-world experience in civil rights law.

Leventhal, as a member of the LSCRRC chapter at New York University School of Law, volunteered to work in Jackson, Mississippi, for LDF during the summer of 1965.

"Mississippi was just the hardest place to work, and I said I would go," he said. Other law students went to places like Alabama or Georgia, "but I went to the Mississippi office, and it was the best decision in my life, without a doubt."

His friends and family were more apprehensive.

"They couldn't believe it. My mother was in tears," Leventhal said. He assured his mother that he was doing "important work."

It was a year after Freedom Summer, during which three young civil rights workers were abducted and murdered in Neshoba County, Mississippi. One of the activists was a local Black man from Meridian, and the other two men were Jewish and from New York, like Leventhal. Their deaths shocked and outraged the country and illuminated the dire consequences of racial inequities in the Deep South. Nevertheless, Leventhal was determined to go to Mississippi, and the adversity only strengthened his convictions.

"I thought this would be my life's work. It's what I wanted to do," Leventhal said. "I never saw it as heroic. I thought it was something I wanted to do, that I had to do."

More than a half-century later, Leventhal still had vivid memories of his first time in Mississippi, which he called "alien" and "frightening." He drove to Mississippi with a car full of people, who dropped him off at the "rickety" LDF office on Farish Street in Jackson. The office was modest, with a small group of lawyers and administrative staff who worked at cubicle desks made of plywood. Marian Wright, who directed LDF's Jackson office and later founded the Children's Defense Fund in Washington, D.C., was in the office when he arrived. She and LDF attorney Henry Aronson encouraged Leventhal's growth as a lawyer.

Marian Wright Edelman (right), the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi bar, organized LDF’s office in Jackson, Mississippi, where she handled more than 120 cases generated during the Freedom Summer. Also pictured are LDF's then-Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg (left) and Richard Hatcher (middle), then mayor of Gary, Indiana.

Wright was "a dynamo in complete control, who was on a mission—very smart," Leventhal said. "But she was the boss, and I needed that. And I'm grateful that I had the opportunity to work with her. One of the highlights of my life was that later, many, many years later, she introduced me as her law partner to somebody, and I was thrilled that she saw me as that. ... That was a privilege."

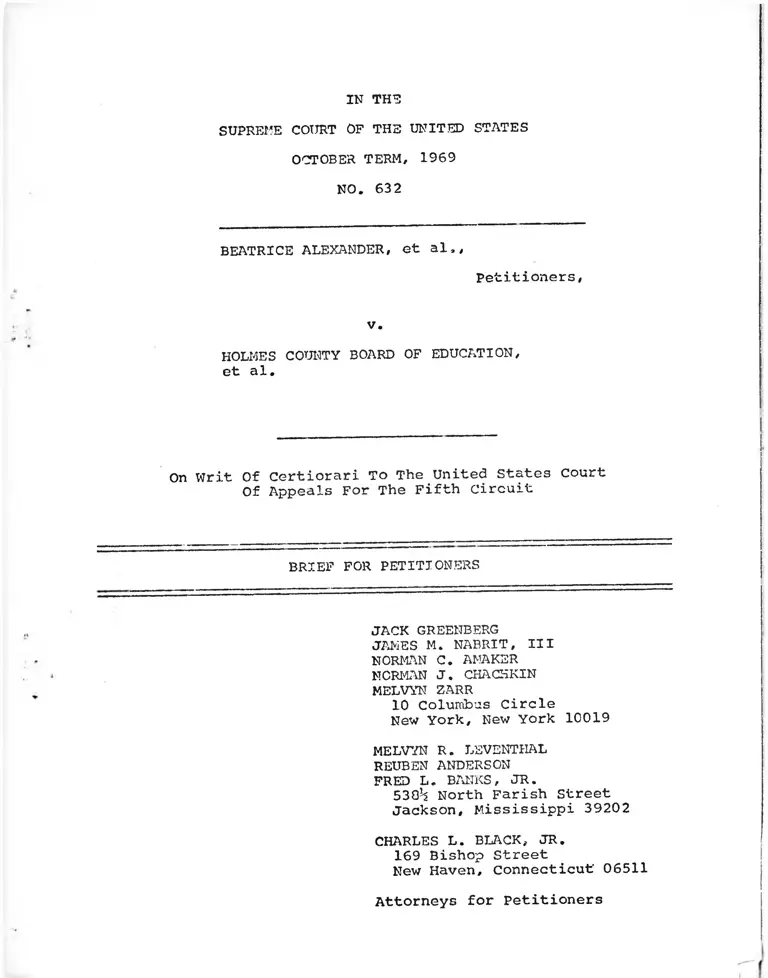

His first assignment was in Holmes County, gathering statements and retainer agreements from potential plaintiffs in a school desegregation lawsuit that would eventually become Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education. A decade after the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the desegregation of public schools with "all deliberate speed" in Brown v. Board of Education II, public schools across the country had nonetheless set up roadblocks and resisted integration. Black parents in Mississippi grew increasingly frustrated with the school districts' foot-dragging. Many school districts in the South developed "freedom of choice" plans, which purportedly gave parents the choice of where to send their children to school. The result was a dual system based on race, with only a handful of Black students enrolled in predominantly white schools. Fortunately, Holmes County had an active civil rights community that included Black parents brave enough to challenge the state's educational status quo despite the risks.

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education Brief for Petitioners

"The case itself, as the larger monumental case, started with the United States asking for more time to desegregate schools," Leventhal explained. "We were at a point where we had all of these school districts under a court order to develop plans to fully integrate their schools, to move from 'freedom of choice' to totally nondiscriminatory schools. The problem with 'freedom of choice' was that the burden of desegregation was imposed on the Black community, when it should have been imposed upon the school district."

Leventhal visited several counties, speaking at churches and community centers. It was dangerous work. Threats of violence against both Black and white activists by white supremacists were common, and Leventhal could not guarantee weary parents that they or their children would be safe.

"I remember driving into Lexington, which is the county seat [of Holmes County], and on every utility pole, just one after the other, was a flyer which said, 'Here are the names of the children integrating the Lexington school,'" Leventhal recalled. "That flyer, I took down. I stopped, took down a couple. ... And you realize as you look at this flyer the danger that these parents had exposed themselves and their children to. And what it does for you is it makes you humble. It makes you realize that, you know, whatever I faced was nothing."

In each county, he made the same pitch: "My themes were, 'Put your children where the money is. These children have to grow up learning that we're equal, that there are strengths and weaknesses in every individual. We are more alike than different.'"

Throughout law school, Leventhal spent his breaks interning in Mississippi. In 1966, he served as LDF's liaison to civil rights activist James Meredith's march from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, working with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders.

In 1967, Leventhal graduated from law school and also married writer and activist Alice Walker, whom he had met in Mississippi. When they moved back to Mississippi shortly after, they became the first legally married interracial couple in the state.

Alice Walker and Melvyn Leventhal hold their daughter, Rebecca.

Getty Images, Bettmann/Contributor

The Arc of the Moral Universe

Leventhal, along with Reuben Anderson, Fred Banks, and John Nichols, formed Mississippi's first interracial law firm in Jackson. He worked there for two years before becoming a full-fledged LDF lawyer. As a dedicated civil rights attorney, Leventhal was literally and figuratively under the watchful eye of white supremacists. On two separate occasions, members of the Ku Klux Klan left business cards on his porch that read, "The eyes of the Klan are on you," with an image of two eyes.

"I was angry," Leventhal said. "I cannot get over the fact that I reacted more with anger than fear."

Although Leventhal got a German shepherd dog to watch his house and kept a rifle in his car, he believed his work was bigger than the risks. He was also inspired by the courage of his Black clients, many of whom had also received intimidating business cards from the Klan.

"My clients were out in these rural counties, getting such business cards," Leventhal said. "You know, they were the source of strength for me. And if they could do it, and I'm in Jackson, and I'm a lawyer protected by the court system, how can I not do it? ... How can I not be behind the people who are experiencing it in a much more dangerous manner?"

Despite the threats of racist violence, Leventhal said a large community of white people who opposed racism also lived in Mississippi.

"I learned in going about Mississippi that there was far more diversity in the attitudes of the white community than we really appreciated," he said. "We had in the Northern District of Mississippi judges who were much more responsive to our claims, either because they felt they had a duty as judges—they had signed an oath and they were bound by it—or because they felt strongly about the issues and they were 'moderates.'"

In 1969, Leventhal rejoined LDF as a full-time lawyer. He served as LDF's lead counsel in Mississippi until 1974. When Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education reached the U.S. Supreme Court in October 1969, Leventhal played a key role.

After U.S. government officials in the Nixon administration changed their position and announced that they supported additional delays in school desegregation, "I made it a political issue," Leventhal said, laughing. "I filed a 'motion to realign the parties'—that is, I said I wanted the United States to be a defendant because it had moved against the clients' [Black students'] best interest. And in fact, the government was no longer advocating [for] desegregation or unitary systems, and therefore, they should be a defendant in the case."

New York Times civil rights reporter Roy Reed wrote a front-page article about Leventhal’s efforts, turning Alexander v. Holmes County into a national story. A team of LDF lawyers, including several in New York, worked on the briefs. LDF Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg argued the case before the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that the school districts' delay in desegregating classrooms violated Brown's mandate. The per curiam decision stated that "each of the school districts here involved may no longer operate a dual school system based on race or color" and that the districts must "begin immediately to operate as unitary school systems within which no person is to be effectively excluded from any school because of race or color." The Court's order of immediate integration eclipsed the "all deliberate speed" standard.

The case also received the support of the Black community and other allies. Leventhal called the day of the oral argument "amazing."

"The crowd circled the block," he recalled. "We had a huge turnout for the oral argument—very supportive of our position. To me, it illustrates the role of non-legal issues in the way that determine the outcome of cases. I think that circumstances came together, which, as I say, I initiated through [my] motion [to make the United States a defendant], making it a national story. And then, we all converged on it and made it happen."

But in the aftermath of the Alexander ruling, white families fled from the public school system and enrolled their children in private schools that sprouted across the state. Leventhal said he did not anticipate the growth of all-white private schools, which "frustrated" and "saddened" him.

Despite this disappointing development, Leventhal pointed to a sentiment from 19th century theologian Theodore Parker (and later popularized by Martin Luther King Jr.): "The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice." As Leventhal elaborated in the 2023 interview, "I believe that, ultimately, each generation improves significantly from its positions, its philosophy of life, from what's moral and immoral, to some extent—and that it's just a necessary part of progress."

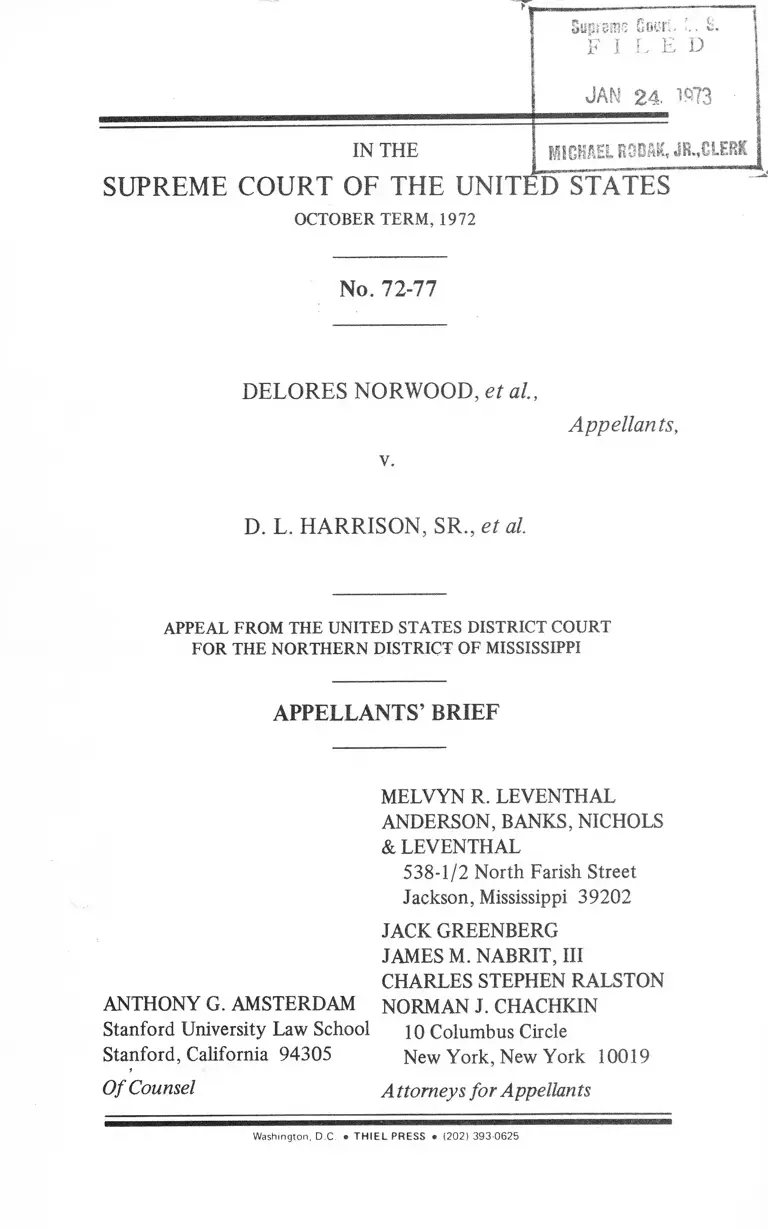

Textbook Justice

As all-white private schools proliferated in the wake of Alexander, the state of Mississippi loaned free textbooks to students in both public and private schools under a program that began in 1940. LDF filed a class action lawsuit, Norwood v. Harrison, arguing that under the U.S. Constitution, states may not offer financial aid or the equivalent textbook-lending program to private schools that discriminate on the basis of race. LDF's lead plaintiffs included Delores Norwood, a Black student who said that by supplying textbooks to these private schools, the state provided direct aid to racially segregated education.

Norwood v. Harrison Appellants' Brief

"I took depositions all over the state of Mississippi to establish that these academies were segregated and that they were discriminating," Leventhal said. "So, I was able to compile a brief which contained a great deal of information on a vast number of private segregationist academies. ... The record I needed to establish was that they were discriminating. Private schools have every right to exist, but that they had been set up to circumvent, to escape, the obligations of the public school systems."

However, in 1972, a three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Mississippi rejected Leventhal's reasoning and ruled that Mississippi's program did not promote racial segregation.

In February 1973, Leventhal argued Norwood v. Harrison before the U.S. Supreme Court, seeking to eliminate the textbook aid. He was still a young lawyer at 29 years old, but Greenberg was prodded by his deputy, James Nabrit III, to let Leventhal stand before the high court. Leventhal considered Nabrit his mentor at LDF, and Nabrit served as the second chair while Leventhal delivered oral arguments.

Excerpt of oral arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court in Norwood v. Harrison

"There is a moment in an oral argument where some judge is baiting you, either to help you or hurt you," Leventhal said. "And [in Norwood] the [justice's] question was, 'Are you saying that all private schools—all of these schools—not one of them is entitled to state textbook assistance?' And I said, 'No. I'm saying those that discriminate.' If I hadn't answered that question the way I did, I might have lost the case, or part of the decision would have been more hostile. And I remember, personally, Jim said to me, 'That was the question.' You have to be careful. That's what I remember about the argument. And you've got to make sure you don't lose the case at oral argument."

Leventhal explained the importance of preparation before arguing a case: "The hard part is to not get hit with a question that you can't answer because you've [not] already thought of it."

The strategy and preparation paid off: In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court vindicated LDF's position, holding that state textbook assistance to private schools that discriminate on the basis of race was unconstitutional.

LDF’s Legacy

Leventhal moved back to New York in 1974, where he served as a staff attorney at LDF's office at 10 Columbus Circle until February 1978. He then joined the Carter administration in Washington, D.C., serving as the Deputy Director of the Office for Civil Rights in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare until April 1979. Afterward, he returned to New York City and served as the Assistant Attorney General of New York in charge of the Consumer Frauds and Protection Bureau, and then as the Deputy First Assistant Attorney General in charge of litigation brought against the state of New York and its various agencies. He has been in private practice in New York City since 1984.

Although he left LDF and government service, he never left the struggle for civil rights. Even in private practice, he worked on civil rights cases.

"I always had civil rights cases on my docket, and I always found them important," he said. "Near the end of my career, I had fewer. I became an art lawyer, primarily, representing some very special people, very prominent individuals and companies. And I always was an advocate for, and always welcomed and did a lot of pro bono stuff that no one knows about. So, I think it's always been a part of my life. It's always been something important to me. It's just part of my nature."

Reflecting on his career at LDF, Leventhal lauded the organization as "the finest, most important civil rights law firm in the history of the country." He continued, "I think that there should be far more attention paid to the long history and the cases that came before you. I think that's always important, and I'd like to see more of that. I'd like to see more reaching back to the communities and the lawyers who worked in that era because it's part of history and part of success that is overlooked."

Read more about resistance to Brown v. Board of Education II and "all deliberate speed"