Smith v. Allwright: The LDF Voting Rights Case That “Changed the Whole Complexion of the South”

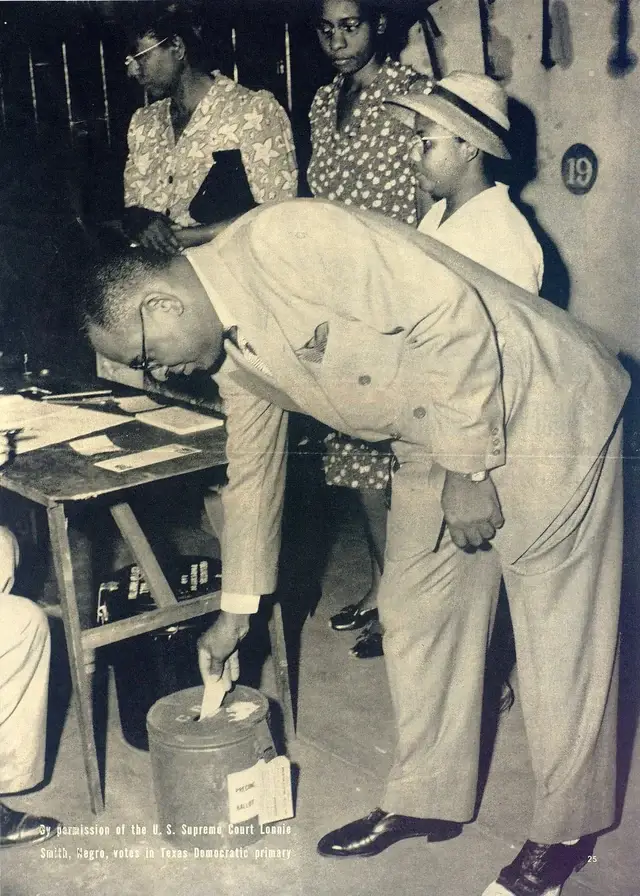

On July 15, 1940, 39-year-old Dr. Lonnie Smith, a Black Houston dentist, went to the Harris County Clerk’s office and asked for an absentee ballot so that he could vote in the upcoming Texas Democratic Party primary election. Election officials turned Smith away because he was Black. One month later, when the primaries led to a run-off election, Smith returned to the clerk’s office, showed his poll tax receipt, and asked for another ballot. Officials again said no.

Even though the U.S. Constitution’s 15th Amendment prohibited federal and state authorities from denying citizens the right to vote “on account of race,” the Texas Democratic Party denied Black people voting rights in primary elections—an overtly discriminatory rule permitted by Texas law at the time. For 16 years, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had protested this conflict between federal law and state party practice. In fact, in three earlier cases—Nixon v. Herndon, Nixon v. Condon, and Grovey v. Townsend—Black voters from Texas filed lawsuits that reached the Supreme Court on appeal. Twice, the plaintiffs won, but that did not stop the Texas Democratic Party from finding loopholes to deny the Black vote.

Thurgood Marshall and the Smith v. Allwright Complaint

In the fall of 1940, Thurgood Marshall, who had recently founded the Legal Defense Fund (LDF) as the litigation arm of the NAACP, went to Texas to file a complaint on Smith’s behalf. At the time, Marshall was 32 years old and had served as NAACP counsel for four years in New York City. The complaint contended that S.E. Allwright, the Election Judge of Harris County, and James E. Liuzza, the Associate Election Judge of the 48th Precinct of Harris County, had refused to allow Smith to cast a ballot in an election that would nominate Democratic candidates. Marshall argued that the election officials had violated federal laws that prohibited denying citizens the right to vote based on their race, color, or previous condition of servitude. He also asserted that the officials’ actions violated the 14th, 15th, and 17th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

This was the start of Smith v. Allwright, a case that would eventually lead Marshall to argue before the Supreme Court for the first time. On April 3, 1944, the Court’s eight-to-one decision in favor of Smith would declare that the all-white Texas primaries were illegal, changing voting rights in America. No longer would the state of Texas or its election officials be able to evade the language of the Constitution to discriminate against Black voters.

Before producing a landmark precedent, however, the case had to start with a Black plaintiff courageous enough to fight powerful white officials in the Jim Crow South. When Smith agreed to represent generations of Black Texans who had been denied their voting rights, he—a lifelong Texan and an officer of Houston’s NAACP chapter—knew the history of violence targeting Black activists in his city and state.

A Legacy of Black Activism

Smith’s fight for voting rights in the 1940s continued a legacy of Black activism dating back to the Reconstruction Era. From 1865 to 1877, formerly enslaved persons were guaranteed equal rights as citizens through the ratification of three Constitutional amendments. Progress was far-reaching: After Congress ratified the 15th Amendment in 1870, more than half a million Black men registered to vote. This led to the election of nearly 2,000 Black officials throughout the South and, over the next two decades, the formation of multiple Black civic groups like the Colored Farmers’ National Alliance, a union of over one million Black workers founded north of Houston in 1886.

The surge in Black political power led to violent resistance from the Ku Klux Klan and other similar white supremacist organizations. In 1903, when Black Houstonians boycotted railroads to protest segregation, angry white voters in Texas pressured officials to repeal the Black vote. That same year, state legislators passed a law that allowed party conventions to include race among primary voter qualifications. Some counties, particularly those with large cities and substantial Black populations, invoked the law to exclude Black people from voting in primary elections.

Smith came of age in a time and place rife with racial bigotry. In 1906, when he was 5 years old, Houston’s Jim Crow laws frustrated visiting Black soldiers who served with the 25th Infantry, an all-Black Army regiment commanded by white officers. When fights broke out between Black soldiers and white civilians, President Theodore Roosevelt dishonorably discharged 167 Black soldiers—including Medal of Honor recipients—despite a lack of evidence of any wrongdoing by those who were punished.

When Smith was 16 years old, political outrage flared up again during the Houston Race Riot of 1917. After more than 100 members of the all-Black Third Battalion, 24th Army Infantry Regiment (different from the 25th Infantry) staged a mutiny following an assault of Black military officers, a tribunal led to the largest court martial and the largest mass execution of American soldiers in Army history. Within a few years, Houston’s racial turmoil turned the city into a legal battleground for civil rights.

Smith established his dental practice in Houston soon after graduating with his doctorate in dentistry in 1924 from Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee. At that time, Black Houstonians were reacting with intense frustration to the state’s new discriminatory election law. While Texas counties could decide who voted in primaries prior to this law, the 1923 statute eliminated all Black citizens from the voting rolls. It read, “In no event shall a negro be eligible to participate in a Democratic party primary election held in the State of Texas, and should a negro vote in a Democratic primary election, such ballot shall be void and election officials are herein directed to throw out such ballot and not count the same.” Because the Democratic Party dominated Texas politics at the time, the primary vote counted more than the general election vote.

Lonnie Smith votes in the Texas Democratic Primary.

"In no event shall a negro be eligible to participate in a Democratic party primary election held in the State of Texas, and should a negro vote in a Democratic primary election, such ballot shall be void and election officials are herein directed to throw out such ballot and not count the same." - 1923 Texas Election Statute

The NAACP’s Legal Strategy: Nixon v. Herndon and Nixon v. Condon

For decades, Black Texans had endured Jim Crow laws and discriminatory voting practices. They grew tired of paying poll taxes and taking literacy tests, understanding that the requirements’ sole purpose was to discourage their political participation. It was time to mobilize—and by the mid-1920s, Black Houstonians had sufficient resources to do so. A strong post-World War I economy fostered a growing Black middle class that could pay the membership dues to join groups like the NAACP.

Founded in 1909 in New York City as a political action organization, the NAACP’s mission was to obtain full citizenship rights for Black Americans. By 1940, the NAACP had more than 350 branches and approximately 50,000 members. Most members lived in the South, where deep-seated institutional racism and frequent racial violence created the most urgent need for organizing around a targeted legal strategy.

Just months before arriving in Houston to meet with Smith, Marshall drafted a corporate charter to create LDF, a charitable organization for non-lobbying activities and the NAACP’s litigation arm.

Prior to Smith’s case, the national NAACP branch in New York City had provided financial support, but not legal representation, to the Black plaintiffs in the three earlier Texas primary cases: Dr. Lawrence Nixon in Nixon v. Herndon and Nixon v. Condon, and Richard Randolph Grovey in Grovey v. Townsend. When Marshall arrived in Houston in 1940 to represent Smith in his legal challenges, he had to contemplate a different strategy, as prior approaches had failed to halt the blatant discrimination in Texas.

The Smith case bore strong similarities to the lawsuit brought in 1924 on behalf of Nixon, a Black physician from El Paso. In Nixon v. Herndon, which reached the Supreme Court in January 1927, Nixon’s lawyers argued that the 1923 Texas statute allowing discrimination was invalid and violated the 14th Amendment’s admonition that, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States… nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Nixon’s legal team also argued that the Texas law violated the 15th Amendment, which prohibited governments from denying a citizen’s right to vote “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Voters at a polling station in Dunn Loring, Virginia, on November 8, 1960. (Photo by Edwin Huffman/United States Information Agency/PhotoQuest/Getty Images)

Two months later, Nixon and his team of lawyers had a victory. Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. said that in enacting the 1923 statute, Texas violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. However, the judgment did not address whether a primary counted as an “election” or whether the 15th Amendment protected a citizen’s right to vote regardless of race. “We find it unnecessary to consider the Fifteenth Amendment,” Justice Holmes wrote, “because it seems to us hard to imagine a more direct and obvious infringement of the Fourteenth.”

Texas officials nonetheless found a way around the high court’s opinion. The Supreme Court had said that states could not enact laws that denied the right to vote based on race. In response to the Supreme Court’s decision, Texas transferred the power to decide voter qualifications to the Texas Democratic Party, a so-called “private” organization. In passing the law, Texas hoped to circumvent the 14th Amendment, which required state action.

So, when Nixon went to vote in the 1927 primary a few months after his Supreme Court victory, he was again rejected based on his race as a Black man. Nixon filed another lawsuit. Once again, he had the financial support of his local NAACP chapter, other local Black civic groups, and the national NAACP. This time, he hired Black attorneys from a Houston law firm. Reaching the Supreme Court in 1932, Nixon’s legal team argued in Nixon v. Condon that the state of Texas had adopted unconstitutional measures to keep Black voters from participating in primaries. In a five-to-four decision, the Court again sided with Nixon. It agreed that the state had not acted lawfully in delegating power to the Texas Democratic Party to decide primary voter qualifications.

Yet again, Texas officials created another route to avoid compliance with the 14th Amendment. At the next convention of the Texas Democratic Party, the executive committee passed a resolution limiting party membership to “white Democrats” only. Now, a Black voter could not identify as a Democrat, and therefore could not vote in the Democratic primary. Months after his second Supreme Court victory, Nixon was once again refused a ballot to vote in the Democratic primary.

"No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States… nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

- Second clause of the 14th amendment, u.s. constitution

Grovey v. Townsend

In 1935, a fearless Black activist and barbershop owner in Houston named Richard Randolph Grovey mounted yet another campaign against Texas’ discriminatory primary rules. Grovey’s passionate advocacy rallied a host of lower- and middle-class Black Houstonians to donate to the Grovey Primary Fund.

"We plan to use reason, the public press, and the courts to let the world see Texas democracy as it really is," Grovey declared.

The national NAACP wanted Grovey and his supporters to wait. NAACP Executive Secretary Walter White and his board feared that the Supreme Court of the mid-1930s—conservative and at odds with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s progressive New Deal programs—would rule against any civil rights lawsuit that was not meticulously planned. White said that the New York City office was planning a legal challenge to the Texas primary rules, but his team wanted to wait until they had the right client at the right time. He warned Grovey’s lawyers that a loss would reverse any small benefit made by the previous victories. Grovey moved ahead anyway.

On April 1, 1935, a unanimous Supreme Court ruled against Grovey. Citing a recent Texas Supreme Court ruling, Justice Owen Roberts said the state had the right to allow private associations like political conventions to decide the qualifications of their members. To justify its position, the U.S. Supreme Court distinguished between the illegal denial of the right to vote and what it considered the permissible refusal of party membership. What the national NAACP had feared came to pass when the nation’s highest court ruled that the exclusion of Black voters from political parties did not violate the Constitution.

Smith v. Allwright

Marshall would be the next to take on this fight, once he and the NAACP had more fully prepared the stage. Both Marshall and White traveled throughout Texas to strengthen the relationship between NAACP chapters and the organization’s headquarters in New York. A gifted fundraiser, Marshall also generated support at statewide NAACP meetings. He urged Black voters to come together and donate to the Democratic Primary Defense Fund, which raised more than $200,000 for Smith’s case. Local NAACP chapters supported lobbying efforts by collecting information for press statements and articles that highlighted the plight of Black citizens in the South, where less than 1% of eligible Black voters had registered to vote. Providing context about the many forms of bigotry in Texas, NAACP branch secretaries reported that factories and shipyards in the state would not hire Black people as skilled workers, and postmasters refused to distribute Black newspapers. Between 1940 and 1944, NAACP chapters sent numerous affidavits from Black voters to the Department of Justice stating that election officials in Texas, Arkansas, and South Carolina had denied them voting rights.

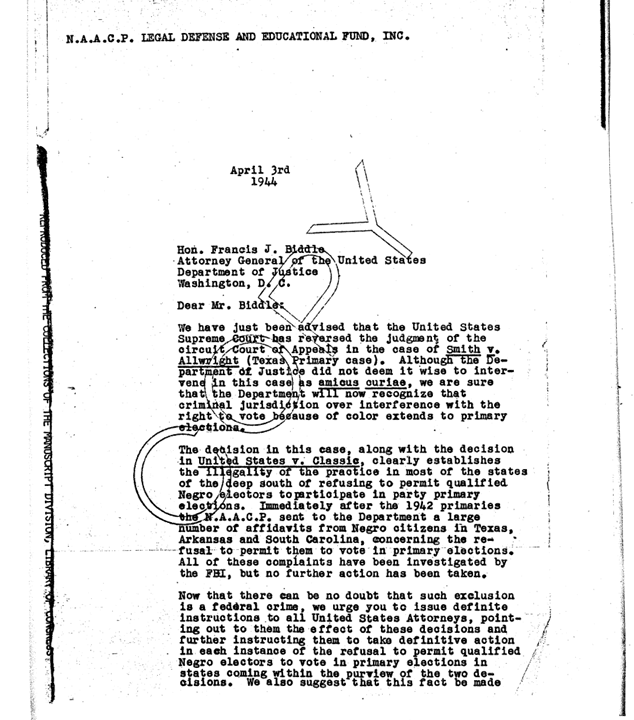

Correspondence between Thurgood Marshall and U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle, April 1944

This item is part of the Library of Congress’ LDF collection Item 3 (Folder 001517_011_0359_0001) pages 37 and 38

Marshall and his co-counsel, most notably former and future federal Judge William Hastie, argued that regardless of which agency decided voter qualifications, any racial primary restriction denying Black citizens the right to vote violated their Constitutional rights. As Smith’s legal team developed its argument, they studied the 1941 case United States v. Classic, which the Justice Department’s newly formed Civil Rights Division had brought to the Supreme Court. In Classic, Herbert Wechsler argued that election officials in Louisiana had “willfully” altered and falsified primary ballots by ignoring votes cast by white voters. Because election officials operated under state law, said Wechsler, their behavior violated the rights of American citizens—even in primary elections, and especially in one-party states like Louisiana and Texas, where “primary results were tantamount to election.”

On June 7, 1943, the Court agreed to hear Smith v. Allwright. Fortunately for Smith and other Black Texans, appointments by President Roosevelt meant that the Supreme Court had a more liberal bench than it had in 1935, when it decided Grovey v. Townsend.

Ahead of Marshall’s opening argument in November 1943, the NAACP continued building political support for its case by securing friend-of-the-court (amicus) briefs from the American Civil Liberties Union, the National Lawyers Guild, and the Workers Defense League. Marshall and his co-counsel, including Hastie and W.J. Durham, a Black lawyer from Texas, meticulously prepared for the case. Under Marshall’s leadership, LDF developed a practice of taking cases through intensive “dry runs.” In his memoir Crusaders in the Courts, Jack Greenberg, who succeeded Marshall as the second Director-Counsel of LDF, wrote that Marshall’s teams argued their Supreme Court cases “at Howard Law School before a panel of lawyers and professors who asked every imaginable question they thought might come from the Court.” Marshall entered the courtroom confident that whatever questions the Supreme Court justices might pose, he had already considered, debated, answered, revised, and redelivered them before some of the sharpest legal minds in America.

On November 10, 1943, in front of a packed courtroom, Marshall’s team presented the argument they had honed for years: Given that primaries were a controlling factor in elections, the Texas whites-only primaries were unconstitutional because they ultimately undermined the Black vote.

Black voters eagerly awaited the Court’s decision: NAACP chapters, civic groups, and individuals across the country sent hundreds of requests to NAACP headquarters for copies of the decision as soon as the Supreme Court issued it. On April 3, 1944, the Court ruled eight-to-one in favor of Smith, overturning its decision in Grovey v. Townsend.

“The United States is a constitutional democracy,” Justice Stanley Reed, a Southern Democrat and the author of the majority opinion, read from the bench. “Its organic law grants to all citizens a right to participate in the choice of elected officials without restriction by any state because of race.” Relying on the 15th Amendment, the Court decided that the statute allowing the Democratic Party to select its members was “state action” that resulted in unlawfully denying Black citizens the right to vote.

The Lasting Impact of Smith v. Allwright

Victory celebrations came swiftly. So did white cries of injustice. Democratic committee chairmen in Georgia and Mississippi said they would ignore the ruling, and the Houston Chronicle reported that Texas officials vowed to increase poll taxes and more strictly enforce literacy tests. Other criticisms of the Smith v. Allwright ruling spoke to the real reason behind the discriminatory voting practices: “The South will allow nothing to impair white supremacy,” insisted Democratic Senator Claude Pepper of Florida. “The South, at all costs, will maintain the rule of white supremacy,” said Democratic Senator John Overton of Louisiana. “The white people of the South will not accept these interferences,” declared Democratic Senator Burnet Maybank of South Carolina.

The NAACP had anticipated a defiant response from white officials. The very day that the Court announced its decision, the NAACP disseminated an action plan to capitalize on the historic ruling. Concerned that enhanced poll taxes and literacy tests would accelerate voter intimidation, Marshall sent a letter to Attorney General Francis Biddle asking him to “issue definite instructions to all United States Attorneys, pointing out to them the effect of these decisions and further instructing them to take definitive action in each instance of the refusal to permit qualified Negro electors to vote in primary elections in states coming within the purview of the two decisions.” To put further pressure on the Justice Department to enforce the law and to hold Attorney General Biddle accountable, NAACP headquarters issued a press release informing the public of Marshall’s letter.

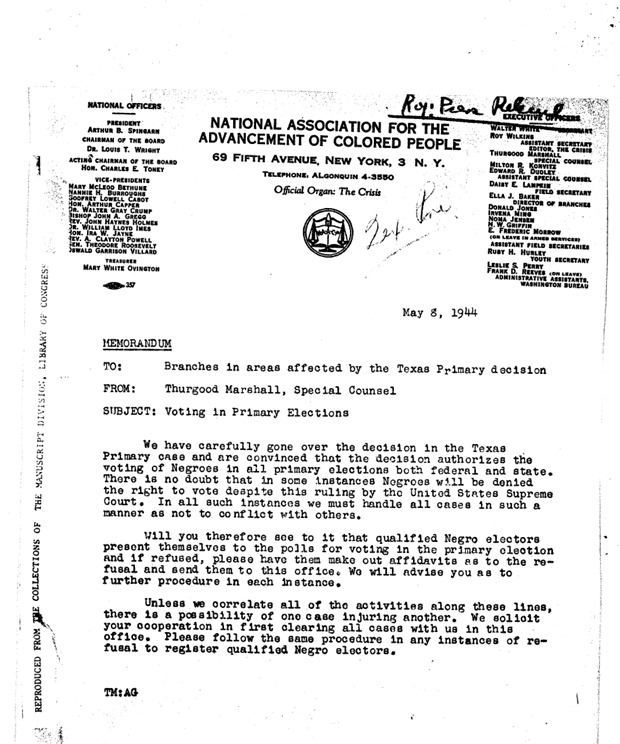

Roy Wilkins, a Black activist and editor of The Crisis, urged NAACP branches throughout the South to seize the moment and “secure the largest possible registration of voters.” Within a month of the decision, as primary season began, Marshall contacted NAACP branches throughout Texas and instructed them to send affidavits to headquarters from any Black voter denied a primary vote. The central NAACP office would aggregate and forward these statements directly to the Justice Department, asking for an immediate investigation.

Memo from Thurgood Marshall regarding Smith v. Allwright's impact, May 1944

This item is part of the Library of Congress’ LDF collection Item 6 (Folder 00157-011-0728) page 15

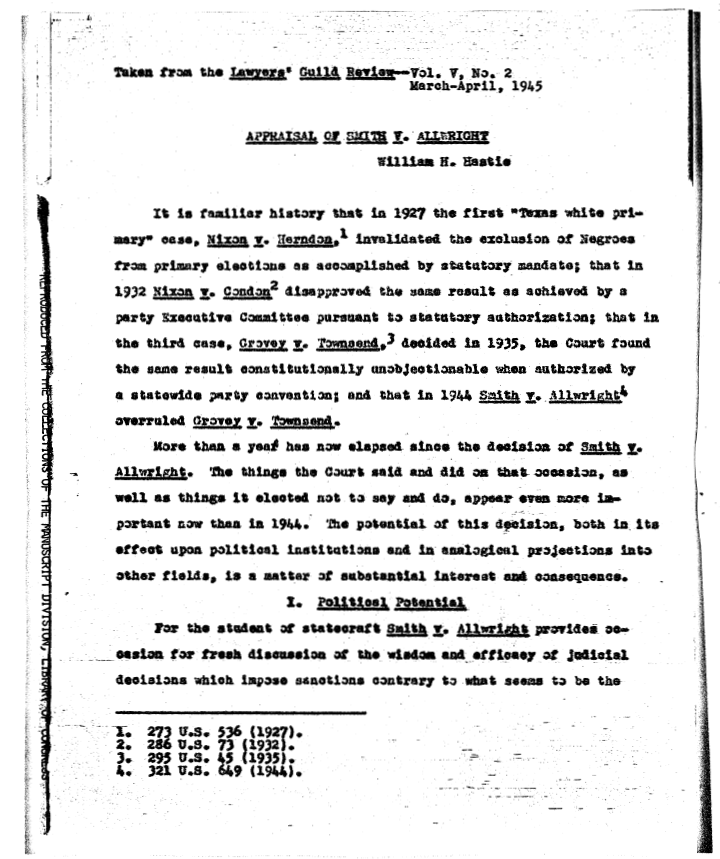

The mobilization plan worked: Smith v. Allwright had an immediate impact in boosting Black voter registration, as did the publicized calls from local NAACP chapters for government accountability and oversight. In 1940, before the Smith decision, 30,000 eligible Black adults had registered to vote in Texas. That number grew to 100,000 in 1947, and 214,000 in 1956. In a 1945 essay for the Lawyers Guild Review, Hastie wrote that since 1944, Texas had not seen “evidence of a widely organized effort to keep Negroes from polls on primary days.”

William Hastie's 1945 essay for the Lawyers Guild Review

This item is part of the Library of Congress’ LDF collection Item 6 (Folder 00157-011-0728) page 15

“I think we have raised hell,” said Durham, Hastie’s co-counsel.

As predicted by Marshall, in time, the Smith v. Allwright ruling changed “the whole complexion of the South.” Throughout the southern states, the case added tens of thousands of Black voters to the rolls of NAACP chapters. It also helped build a Black voting base for U.S. Rep. Lyndon B. Johnson, a future American president who would nominate Marshall as the first Black Supreme Court Justice. Perhaps most importantly, Smith v. Allwright would lay the groundwork in the political battlegrounds of the South for the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

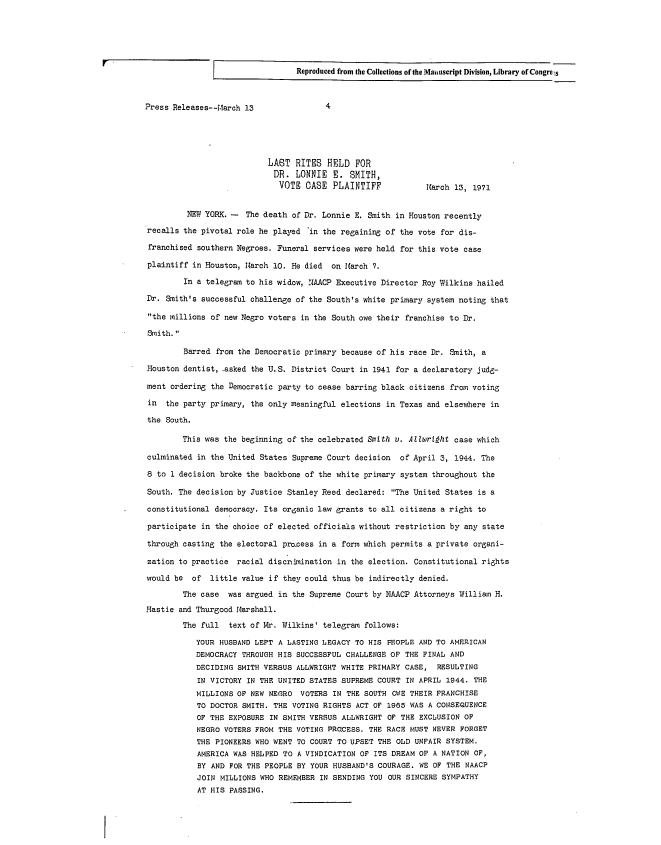

Telegram from Roy Wilkins to Lonnie Smith's widow, 1971

This item is part of the Library of Congress’ LDF collection Item 6 (Folder 00157-011-0728) page 15

In a telegram to Smith’s widow after his death on March 7, 1971, then-NAACP Executive Director Roy Wilkins said, “The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was a consequence of the exposure in Smith v. Allwright of the exclusion of Negro voters from the voting process. The race must never forget the pioneers who went to court to upset the old unfair system. America was helped to a vindication of its dream of a nation of, by, and for the people by your husband’s courage.”

For further reading, see Showdown: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court Nomination That Changed America, by Wil Haygood.