Sylvia Drew Ivie: Connecting Civil Rights and Health Care

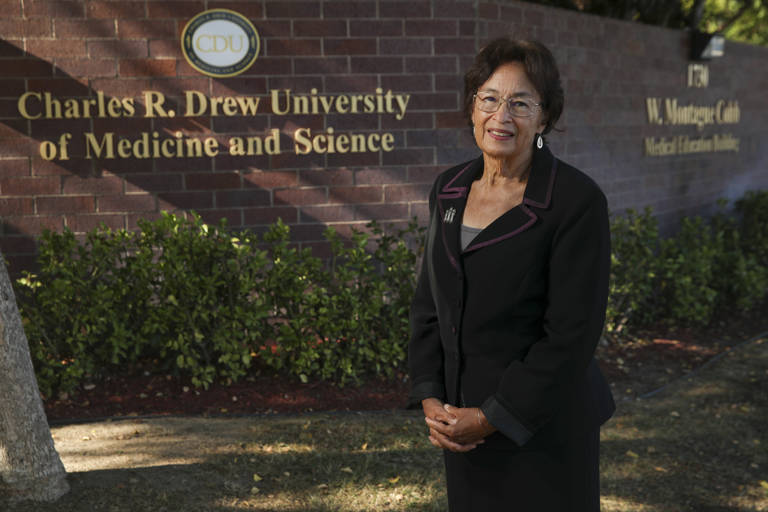

Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

As Senior Special Assistant to the President and CEO for External Affairs of Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science (CDU) since 2016, Sylvia Drew Ivie—who previously worked as an attorney at the Legal Defense Fund (LDF) before shifting to health law—has worn many hats as an adviser, community liaison, and strategic planner. But despite the multiple duties, she is very clear about her underlying mission at the private university in Los Angeles, California, named after her barrier-breaking father.

“My role at the university is to stay connected to the community that founded us, in Watts, L.A.,” she said in a 2023 interview for the Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project.

CDU was founded in 1966 in the wake of deadly riots that swept through the predominantly Black neighborhood of Watts in southern Los Angeles the year before. Like many Black urban neighborhoods in the 1960s, Watts was a food, health care, and housing desert isolated from the thriving metropolis. Many American cities sat on racial powder kegs during that time, vulnerable to any incident that would spark a flame. On August 11, 1965, a fuse was lit in Watts when a white patrol officer pulled over a Black motorist during a traffic stop, and violence broke out. The encounter quickly escalated into a six-day rebellion against police brutality, poverty, and racial inequities, leaving 34 people dead and a thousand buildings destroyed.

In the aftermath of the riots, “the powers that be noticed that there was a place called South L.A. that needed help,” Drew Ivie said.

Fed-up constituents, including many women, consistently attempted to hold officials accountable for the pervasive inequities and neglect. The riots forced policymakers to open their eyes and make changes in the community. Out of that focus and community advocacy came a hospital—named after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.—and CDU.

“We were born in the fire,” Drew Ivie explained of the university.

Also born in the fire was a recognition that health care is a fundamental right and a crucial civil rights issue, a principle that Drew Ivie would champion throughout her career.

Seeds of Knowledge

Drew Ivie was born in Washington, D.C., the third child and youngest daughter of Dr. Charles Drew and Minnie Lenore Robbins Drew. Her father was a world-famous surgeon and medical researcher renowned for his groundbreaking research separating blood and plasma, which could be stored for longer periods of time and used in transfusions in place of blood. The discovery was a medical game-changer that saved the lives of thousands of soldiers and civilians during World War II.

“He had expertise in blood studies, but what he brought to that expertise was skillful organization of people,” Drew Ivie said.

Collaborating with the American Red Cross, he organized the country’s first large-scale blood bank and invented refrigerated bloodmobiles that traveled in communities to collect blood from volunteer donors. Although his innovations revolutionized medicine, they also revealed the racism coursing through many major U.S. institutions—such as the Red Cross itself, which did not accept blood from Black donors. He publicly criticized the policy for being morally unjust and scientifically misguided, and the Red Cross later rescinded the rule. But blood was segregated by race throughout the war.

He also applied his organizational skills in the backyard garden of the family’s house near Howard University, where he was a professor at the medical school. Once, he let Drew Ivie help him plant a tray of red gardenias, which is where she learned one of many life lessons.

“I learned in that process what doing a good job meant,” she said.

After her father dug a hole, Drew Ivie was responsible for planting a flower. But her attention to detail was lacking, and he refused to let her plant the next flower until she satisfactorily planted the first. He explained to his daughter that she needed to pat the soil down so the plant could grow strong and not fall over.

Drew Ivie called her father’s instruction “a powerful lesson, which I’ve always kept with me: Plant the seed I’m planting. Make sure that one grows before I move to the next one.”

Prioritizing Education

Tragically, on April 1, 1950, when Drew Ivie was 6, her father died from severe injuries he suffered in a car accident in North Carolina. Her mother, a former professor, had to raise four children alone with no income and possibly no place to live because they lost their university-provided housing after Charles’ death. But his friends and colleagues raised enough money for a down payment on a house.

Drew Ivie said her mother “was a very strong, enlightened woman, and she did a good job. She got four children through college and graduate school and never had any money.”

The family relied on scholarships and the largesse of friends to help the children get quality educations. “My mother was very good at writing to people and saying, ‘I need help with my children. Their father is gone,’” Drew Ivie recalled.

Drew Ivie was 10 when the U.S. Supreme Court declared segregation in U.S. public schools unconstitutional in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. Before then, she had attended Lucretia Mott Elementary School, within walking distance of their house. At the school—named after the 19th-century suffragist, abolitionist, and social reformer—Drew Ivie said students received a high-quality education from top-notch Black teachers who were not allowed to teach at white schools.

“The best and the brightest [Black] teachers all had to teach in Black schools because they weren’t admitted to white schools,” she explained. “So we had excellent, excellent teachers.”

The students also received personalized care. Many Black educators lived in the neighborhoods where they taught, and they knew their students’ parents. It was not unusual for Drew Ivie’s teacher to contact her mother—for example, to tell her that Drew Ivie could not see the blackboard clearly.

“She called her up,” Drew Ivie recalled. “She said, ‘What about the glasses for Sylvia? I sent that note home. … Could you get her glasses, please?’ So, that’s the kind of relationship they had, which today, I don’t think that would happen.”

Her integrated junior high school also had “wonderful” teachers, and she adapted well to the new environment. But she encountered an unfamiliar social issue: poverty.

“My first friend was a very poor white girl who lived in the neighborhood. And I didn’t know anything about poverty. I knew that some of the people next to my elementary school lived in the projects. And I felt very bad for my friend … because the teacher berated her for not having her hair straightened and fixed before our class pictures. … Even then, I was conscious that maybe her mother couldn’t afford to get her hair done. I thought [it] was very mean to make her feel bad about that.”

Drew Ivie’s older sisters attended the newly integrated Theodore Roosevelt High School. Adjusting to Roosevelt was difficult for them because they had a longer distance to get to school, and only about one-quarter of the student population was Black during their early years there. To avoid the same experience for Drew Ivie, her mother sent her to Oakwood Friends School, a Quaker boarding school in Poughkeepsie, New York, when she was 12. Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, an admirer of her esteemed surgeon father, later paid Drew Ivie’s tuition.

“I had a wealthy white roommate who used to take me home to her big sprawling house in New Jersey, and Mrs. Roosevelt was a friend of theirs,” Drew Ivie said. “And so, I met her at a dinner party at their house. … I called my mom and I said, ‘I met Eleanor Roosevelt.’ And so, my mother just said, ‘Okay, good,’” and then she wrote Roosevelt a letter asking for help, Drew Ivie recalled with a laugh.

Quaker Influence

Sylvia Drew Ivie, Executive Director of T.H.E. Clinic, sits in a waiting room among the MediCal patients that the clinic serves. (Photo by Iris Schneider/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

The Religious Society of Friends, also known as the Quakers, included both abolitionists as well as members who enslaved people in the 17th century. The issue of slavery was widely debated among Quaker communities in North America and the Caribbean, some of whom considered trading enslaved people a necessary business practice. However, in 1688, they became the first religious denomination in North America to denounce slavery. Many American Quakers had prominent roles in the Underground Railroad, shielding and sheltering formerly enslaved adults and children who had escaped.

Oakwood, founded in 1796, instilled in its students the Quaker values of equality, peace, and community. Abolitionist Lucretia Mott was an alumna. Drew Ivie took those values to heart. She recalled attending Quaker meetings, which consisted of sitting in silence for an hour. “We were required to go to Quaker meetings twice a week, so we would sit in silence,” she said. “If you have a thought or a spiritual feeling, then you stand up and speak, and then you sit back down. That’s the way the meeting goes. And people might pick up on that and follow with something, or they might not.” She called the experience “very spiritual and centering.”

Drew Ivie admired the Quaker commitment to serving others. She once faked permission from her mother and took the train from Poughkeepsie to New York City for a weekend expedition helping those in need.

“I took the train down to Harlem and found the American Friends Service Committee office,” she said. “And they took me to an elderly person’s apartment, and we painted it that weekend. And it was exhilarating.”

She also admired the Quakers’ activism and bravery, even after she left Oakwood. For example, to protest the Vietnam War and promote their mission of peace, the organization A Quaker Action Group circumvented U.S. law and sailed into Haiphong Harbor in 1967 to deliver medical supplies to the civilian victims of the war. That act left a lasting impression on Drew Ivie.

“Quakers were always doing heroic things, just very quietly,” she said.

College Years

After graduating from Oakwood, she entered Vassar College. Choosing Vassar was not a particularly difficult decision for Drew Ivie: It was local, and she had attended events there while she was at Oakwood. Most importantly, it was the only college to offer her a scholarship—a prerequisite for her mother.

However, a conflict began before she even arrived on campus. She received a housing questionnaire asking whether she wanted a roommate or a single room. The form noted that single rooms were limited and required a good reason for requesting one. Drew Ivie replied that she wanted a roommate anyway, but, to her surprise, she was given a single room. Angry and confused, she sought answers from the dean, who explained that the school had many Southern white students, and pairing Drew Ivie with one of them would hurt the white girl’s feelings.

“And I said, ‘Well, what about my feelings?’ And I was kind of a shy person. This was very strong language for me. And she said, ‘Well, dear, if you can find somebody who would like to room with you, we’ll be glad to put you two together.’”

But that solution did not go far enough. Drew Ivie demanded the policy be changed, or she would tell the media.

“That was the end of our discussion, and it was the end of the policy,” she said. “But I never liked the school after that. That was such a bad faith introduction to an institution that was trying to teach people to take care of people and be leaders in society.”

During her third year of college, Drew Ivie was invited to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom by Dr. William Montague Cobb, an old friend and classmate of her father who taught anatomy at Howard’s College of Medicine. They sat in the third row, “a stone’s throw away” from where gospel legend Mahalia Jackson sang and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his celebrated “I Have a Dream” speech. The event had a powerful, long-lasting impact.

“It was just absolutely electric,” Drew Ivie said. “It was an immersion experience, just being with all those people of every stripe. … We’d come together to say, ‘Things have to change in this country.’ So, that feeling has always stayed with me—that feeling, that triumph of the people coming together to say, ‘We can do better, and we will do better, and we insist that we do better.’”

After college in 1965, feeding off the enthusiasm of other young Black students eager to become civil rights lawyers to help bring about change, Drew Ivie applied to law school. She was accepted by both Harvard and Howard. But the bitter experience at Vassar had left a painful mark, and Drew Ivie declared she’d “had enough with white schools.” So, she chose Howard, which offered her a scholarship, and returned home to her roots.

Civil Rights Lawyer

Sylvia Drew Ivie speaks at a press conference to announce the launch of the first historically Black four-year medical degree program at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science on October 18, 2022. (Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Being back on the campus where her family once lived “was just embracing,” Drew Ivie said. There were frequent lectures from leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. “And there was a culture of heroism, you know, ‘What are you going to do to help? Everybody here has to help in some way.’”

A year after finishing law school, in 1969, she was hired by LDF Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg as an Assistant Counsel in the New York office. Her mentor, Norman Chachkin, helped Drew Ivie hone her skills writing legal briefs. The job required some travel to Southern cities, where she helped LDF and local counsel like Julius Chambers and John Walker with trial motions and appeals. She particularly admired the dedicated Southern lawyers who worked under the constant threat of violence.

“They were so brave, and I was so inspired by them,” she said. “If somebody blew up my car, I don’t know whether I would have kept doing that work. But they kept doing it. … It’s real heroism.”

Decades later, Drew Ivie still recalled certain cases that highlighted the perils of life in the South for Black people, including Kitchen v. Trustees of the Rex Hospital, a wrongful death suit argued by Chambers in North Carolina. A young Black man was senselessly shot by a white man and denied proper medical care at the hospital, and he later died from his injuries. LDF lawyers representing the victim’s wife argued the case, believing the hospital’s failure to treat him likely contributed to his death. But the lawyers were unable to persuade local Black physicians to be expert witnesses.

“They wanted to do their medical part, [but] they didn’t want to do their civil rights part in court,” Drew Ivie said.

A white Jewish physician was brought down from Washington, D.C., to testify instead. Drew Ivie said that routine action lost the case due to the jury’s anti-Semitic bias.

“Everything about it was ugly. And then the poor [wife]—just went through that whole trial and got nothing for it. … That was my most personal immersion in what it was like to be a Black person in the South.”

By 1974, she had been at LDF for five years and had grown frustrated with appellate courts that increasingly tended to rule against civil rights claims. She had also recently married an aspiring filmmaker, and the newlyweds moved to the West Coast when her husband was offered a career opportunity in California. Once there, Drew Ivie decided to transition into health law.

“When [the appellate courts] started saying no, then it sort of meant that it was a roadblock that I couldn’t get over,” she said. “And that’s really why I switched from civil rights into health law when I came out here [to Los Angeles].”

As she picked up the mantle left by her father by shifting to health care, her experience at LDF shaped her approach to public health and reinforced her commitment to the communities and people that needed help.

“Health care access is a civil rights issue for poor people, for people of color,” she said. “It just hadn’t been framed in that way. But I brought the same ethos that I had to the civil rights in education, to the health care arena. And I would bring cases that would say, ‘This is a violation of the statutory law, and it’s also a violation of constitutional law.’ … So, I did both, and I liked interweaving them.”

Looking back on her time at LDF, Drew Ivie said she reveres the “pioneering work” of the glory days and “the audacity of Black lawyers standing up to power.”

“Thurgood Marshall was the first Director-Counsel, and he was fearless—he was a fearless champion. Jack Greenberg was a tireless, brilliant man. We had cooperating attorneys who were brilliant. … They were just singular kinds of leaders associated with it at a pivotal time in our civil rights history in this country. … Without them, everything would have been different.”

LDF’s role today, she said, is to build on that legacy.

“The battle isn’t over. We’re just in a new stage of it, and the need for [LDF] gets greater as we lose civility.” She said now, people are “getting really ugly in their animosity and hatred. And so, we’ve got to have institutional backup at LDF, and with their local lawyers, to be prepared to fight back.”