Thornburg v. Gingles: The Redistricting Case that Gave Black Voters a Say in Elections

Luciel McNeel, a 63-year-old Black domestic worker, told The Charlotte Observer in 1984 that she had been supporting Black candidates in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, for 22 years. Since registering to vote there in 1962, she had not missed a single election, and she had watched as Black candidates ran for seats in the North Carolina House and Senate at least 14 times. Only two Black candidates—State Senator Fred Alexander and State Representative Phil Berry—had won. McNeel said that more Black candidates would be successful if North Carolina stopped using county boundaries to determine voting districts. As seen in Mecklenburg County, McNeel and other Black voters believed this form of legislative mapping diluted their ability to elect their preferred candidates.

At the time, most of Mecklenburg’s Black population of 107,000 lived in two areas of Charlotte, its largest city. Due to its large population, Mecklenburg was a “multimember district” that could elect multiple representatives to the state legislature. But because 75% of the county’s voting constituency was white, for decades white voters controlled the outcome of elections and continually elected their preferred candidates, who were overwhelmingly white. McNeel said that if the state divided the electoral map into smaller, single-member districts, areas with larger Black populations would have greater access to political participation. “[Majority-Black] districts are one of the greatest things in the world,” she said. “You have a chance to choose the person you like.”

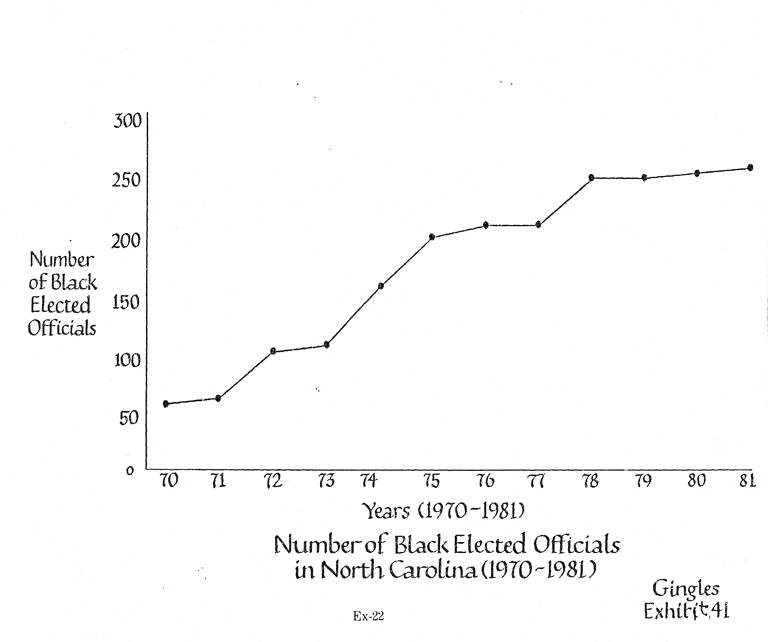

Southern states with such single-member districts had more Black candidates elected to their legislatures. But in North Carolina, county-wide voting enabled white voting blocs to submerge the power of minority voting blocs. North Carolina’s population was 22% Black in the early 1980s, but before 1982, Black elected officials held no more than six of the 170 available seats in the state’s House and Senate. This representation disparity was one of the worst in the South.

“North Carolina is the state that has put up the most resistance to going to single-member districts,” Brian Sherman of the Voting Rights Project of the Southern Regional Council in Atlanta told The Charlotte Observer in 1984. He further explained that “the major obstacle to [B]lack representation has been white bloc voting in combination with either at-large or unfairly apportioned electoral districts.”

In 1985, the Legal Defense Fund (LDF), led by Director-Counsel Julius Chambers and a team of attorneys, challenged North Carolina’s legislative districting in Thornburg v. Gingles. As the first Supreme Court case to test the strength of the 1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, this case advanced equal political participation for Black voters (and, across the country, voters of other races and ethnicities) and established a template for future challenges to racially discriminatory electoral schemes.

Gingles v. Edmisten: The Initial Challenge to Discriminatory Legislative Mapping

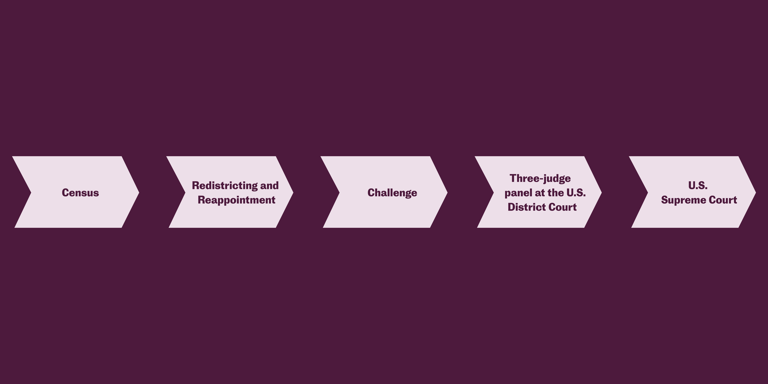

Thornburg v. Gingles started as Gingles v. Edmisten on September 16, 1981. Two months earlier, the North Carolina General Assembly passed a redistricting plan that created seven new legislative districts for the state’s House and Senate—six of which were multimember districts composed of a majority of white voters. Ralph Gingles, a Black lawyer from Gastonia, North Carolina, and three of his Black colleagues (Sippio Burton, Fred Belfield, and Joseph Moody) filed suit in response. They argued that the legislative mapping process led to racially discriminatory electoral results in violation of Section Two of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Section Two prohibits voting practices or procedures that discriminate on the basis of race, color, or membership in minority groups by denying those groups the equal opportunity to elect their preferred candidates. The suit also alleged that North Carolina had failed to submit the electoral changes to the Department of Justice for preclearance, also in violation of the Voting Rights Act.

After the case was filed, Congress passed an amendment to Section Two in the summer of 1982 that clarified and lessened the burden plaintiffs must satisfy to bring a Section Two challenge, like Gingles’ challenge to North Carolina’s legislative redistricting process. Prior to the 1982 congressional amendment, plaintiffs making a Section Two claim had to provide evidence that the legislative redistricting was adopted or maintained with a “discriminatory intent.” The amendment clarified that to prove voting rights violations, plaintiffs need only demonstrate that the results of an electoral process have a “discriminatory effect.”

Mecklenburg County election results in 1982 offered an example of the “discriminatory effect” of at-large, multimember district elections. That year, a Black Democrat named Jim Richardson lost one of the county’s eight representative seats by only 250 votes, finishing in ninth place. Even though Richardson had earned more than 75% of voter support in majority-Black precincts, the county’s overall majority-white voting bloc canceled out that support and thereby diluted Black voter power.

To decide Gingles v. Edmisten, a special three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina considered expert analyses using data from three election years in each of the contested districts. Based on these analyses, the Court found ample evidence of “legally significant racial bloc voting” (also known as racially polarized voting), which is considered key evidence of racial vote dilution. With that and other evidence, the Court ruled in favor of Gingles and his colleagues in January 1984.

Procedural History of Voting Rights Cases

Judge J. Dickson Phillips of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, in a special sitting with the federal District Court, wrote the opinion. In it, he cited “the demonstrable unwillingness of substantial numbers of the [white] racial majority to vote for any minority race candidate or any candidate identified with minority race interests.” The ruling required North Carolina to redraw the contested multimember districts into smaller, single-member districts where Black voters would form the majority and have the chance (not the guarantee) to elect representatives of their choice.

"This is going to make it better for everybody," Gingles told The Charlotte Observer. "It gives everybody an equal chance to participate in the political process."

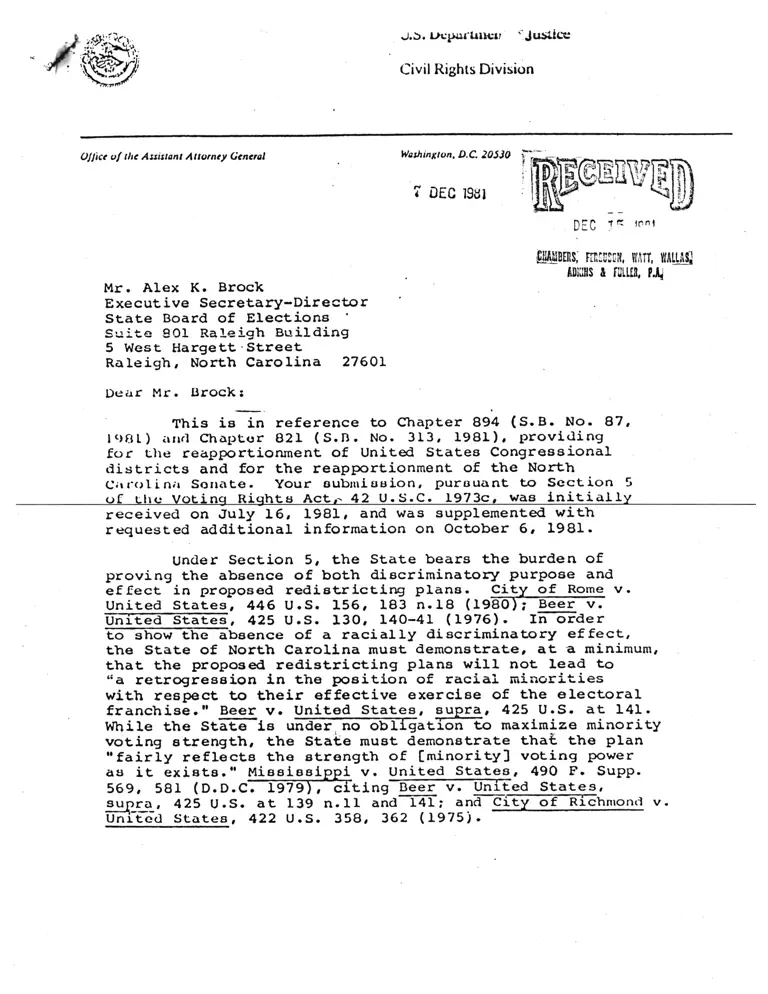

Correspondence from Bradford Reynolds to Brock

North Carolina Appeals to the Supreme Court

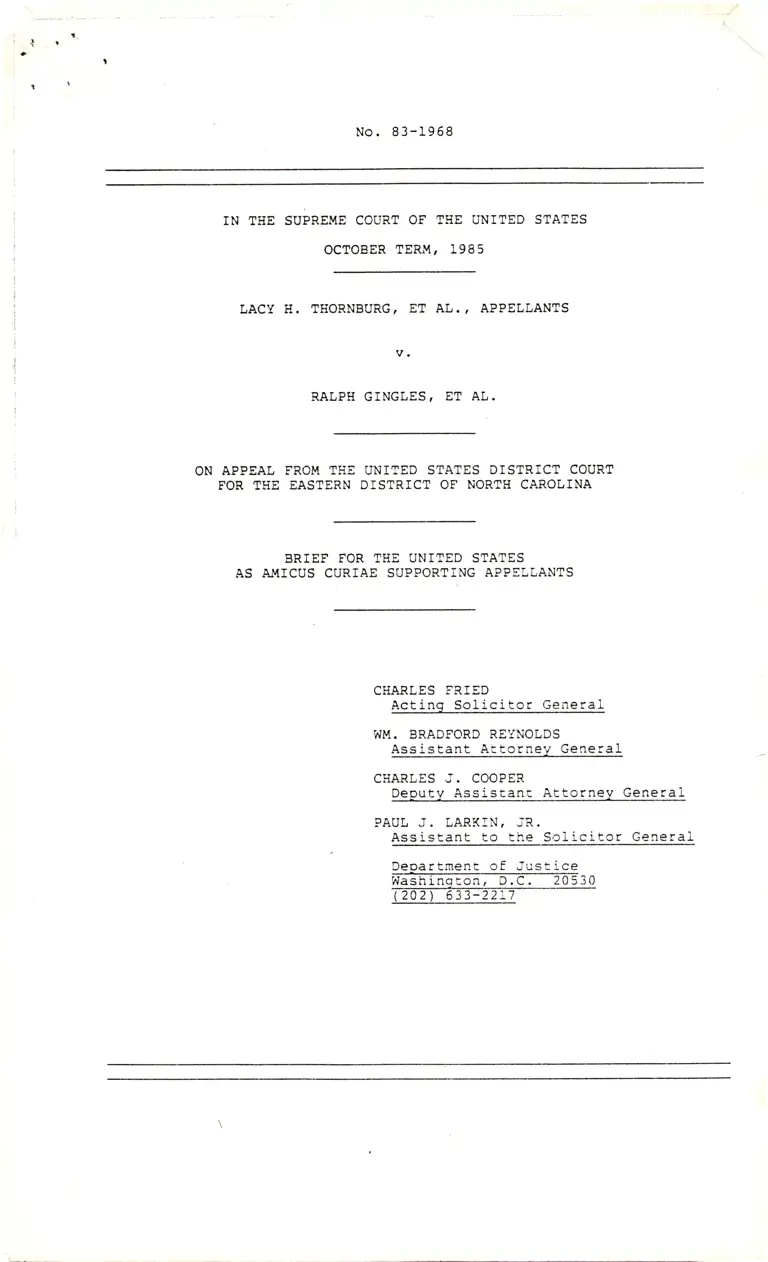

North Carolina and the U.S. Department of Justice under the Reagan administration disagreed with the District Court’s ruling. In 1985, recently elected North Carolina Attorney General Lacy Thornburg appealed the decision directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. Thornburg argued that the District Court had “misinterpreted” the 1982 amendment to the Voting Rights Act. The Reagan administration’s Department of Justice filed an amicus (friend-of-the-court) brief in support of Thornburg’s position, stating that, if upheld, the ruling would indicate that “wherever there has been discrimination in the past and some measure of racial polarization in voting in the present, district courts will be free to strike down virtually any scheme that does not—or even those that do—deliver electoral successes proportional to minority voting strength. That is not what Congress intended.” The brief continued: “Minority voters have no right to the creation of safe electoral districts merely because they could feasibly be drawn. … Nor can it be presumed … that ‘safe’ seats for minority officeholders would necessarily be in the interests of minority voters.”

Gingles’ attorneys urged the Court to affirm that, as plaintiffs proved at trial before the District Court, legislative changes need not be intentionally discriminatory but can still have discriminatory results in violation of Section Two of the Voting Rights Act. The Black voters, represented by LDF attorneys, also urged the Supreme Court to clarify whether the Voting Rights Act guaranteed proportional representation to minority voters and how the Court should determine when racial voting blocs exist. They also pointed to language in Section Two, as amended, requiring courts to weigh “the totality of circumstances” when assessing potential voting rights violations to determine whether minority voters experienced inequality of voting opportunities.

Neither the state of North Carolina nor the Reagan administration believed that the District Court had correctly assessed whether North Carolina’s multimember districts discriminated against Black voters. This position frustrated civil rights groups such as LDF and the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, especially as the appeal resurrected the Reagan administration’s earlier objections to the 1982 Voting Rights Act amendment.

LDF attorney Lani Guinier told The Washington Post in 1985, “We are very concerned that the Reagan appointees in the Justice Department, all of whom opposed the [1982] amendment, may seize this opportunity to try to persuade the [C]ourt to gut the Voting Rights Act.”

On appeal, Thornburg also argued that episodic, minority electoral gains in some of the disputed districts undermined Gingles’ claim under Section Two of the Voting Rights Act. Specifically, after the 1981 redistricting changes, the number of Black legislators in North Carolina had increased to 12, with five coming from multimember districts—notwithstanding Richardson’s 1982 loss in Mecklenburg County.

In response, LDF attorneys argued that these limited numbers of Black electoral successes constituted only 7% of available seats in the North Carolina House and Senate. The evidentiary record that LDF’s Chambers, Guinier, and Eric Schnapper submitted to the Supreme Court included proof of racial bloc voting and racial campaign appeals (i.e., relying on racial stereotypes and tropes to appeal to white voters to not support racial minority candidates) in the contested districts.

The defeat of minority candidates in most elections had wide-ranging impacts: “Legislative positions are not only important in terms of representing [B]lacks in the General Assembly,” Guinier told The Charlotte Observer. “They play an important function in grooming other people for political office and other leadership roles in the community.”

Analyzing the Intent Behind the Amendment to Section Two of the Voting Rights Act

The appeal raised questions about the congressional intent behind the Section Two amendment, which had been authored in 1982 by a bipartisan group of lawmakers. To keep opposition to proportional representation from thwarting the amendment, Republican Senator Bob Dole had brokered a compromise so that the amended Section Two would “protect the ability of minority voters to elect representatives of their choice, provided that it did not guarantee proportional representation.”

Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Appellants

The Justice Department’s amicus brief, authored by Assistant Attorney General William Bradford Reynolds and Acting Solicitor General Charles Fried, said that there were lawmakers opposed to this amendment who claimed the law’s authors represented only “one faction” of Congress. The brief further argued that Congress never intended the law to apply to cases that accused legislators of diluting “minority voting strength” rather than denying their vote outright, such as how literacy tests and grandfather clauses had functioned.

This provoked 10 of the lawmakers who had authored the amendment to file an amicus brief in support of Gingles and his colleagues on August 30, 1985.i Stating that the Gingles case was exactly the sort of dispute they had in mind when passing the amendment, the senators and representatives explained that Congress had “expressly rejected” the current “misguided” position of the Justice Department. They cautioned that if the Court did not uphold the Gingles decision, the government “could raise an artificial barrier to legitimate claims of denial of voting rights.” The same day the lawmakers filed their amicus brief, the Republican National Committee and Republican Governor James G. Martin of North Carolina also filed amicus briefs opposing the Reagan administration’s position.

Motion for Leave to File and Brief of Senators and Representatives as Amici Curiae

On August 31, 1985, The Washington Post wrote that the three briefs “underscored the unusual split between the Reagan administration and much of the Republican Party over the politically sensitive issue. A brief submitted by members of Congress explaining their legislative action to the Supreme Court is extremely unusual.” According to the article, Dole and nine other members of Congress essentially told the Court that “the Reagan administration’s position in a pending voting rights case blatantly misrepresents the purpose of a voting rights bill they wrote three years ago.”

Dole had previously explained in a news conference that one of his “key objectives” in supporting the amendment was to “make it unequivocally clear that plaintiffs may base a violation of Section Two on a showing of discriminatory ‘results,’ in which case proof of discriminatory intent or purpose would be neither required, nor relevant. I was convinced of the inappropriateness of an ‘intent standard’ as the sole means of establishing a voting rights claim, as were the majority of my colleagues on the committee.” During the congressional debate over the 1982 amendment, the Reagan administration had strongly resisted removing “discriminatory intent” from the evidence needed to show voting rights violations and replacing it with “discriminatory results.”

Dole entered the Thornburg v. Gingles case at the request of LDF, telling The Washington Post in 1985, “I think too often we [Republicans] are sort of on the periphery. We’re never really in there when Black Americans need our help.”

A Landmark Victory for Voting Rights

In 1986, the Supreme Court upheld the District Court ruling in a unanimous decision, finding that North Carolina’s electoral process had discriminated against Black voters in its results in violation of Section Two of the Voting Rights Act.

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. delivered the opinion, stating, “Where multimember districting generally works to dilute the minority vote, it cannot be defended on the ground that it sporadically and serendipitously benefits minority voters.”

The decision validated the District Court’s findings that “Black citizens constituted a distinct population and registered-voter minority in each challenged district.” After weighing “the totality of the circumstances,” the Supreme Court agreed that “geographically insular and politically cohesive groups of Black voters” could not “participate equally in the political process” and elect candidates of their choice due to a variety of factors, including multimember districting along with “racially polarized voting,” a “legacy of official discrimination in voting matters, education, housing, employment, and health services,” and “the persistence of campaign appeals to racial prejudice.”

Regarding the argument that the number of Black legislators in North Carolina had increased in 1982, the Court noted a “historical pattern of statewide official discrimination” from 1900 to 1970 in which Black citizens had at times been subject to voting barriers such as poll taxes and literacy tests. These practices, in addition to the problems implicit in multimember district voting, continued to inhibit Black voter registration. The gain of several legislative seats did not reverse the damage that the state’s long history of racial bias—a “complete denial of elective opportunities”—continued to cause to Black voters.

LDF Director-Counsel Chambers told The New York Times that the decision “gives us a powerful new tool for protecting the equal rights of minorities to register, to vote, and to have their votes counted with equal weight.”

Thornburg v. Gingles enabled a level of political participation for minority communities that had previously been denied. Since 1986, Thornburg v. Gingles has been cited in approximately 700 cases related to Section Two of the Voting Rights Act because of the discriminatory effect precedent that it set for district courts to use in deciding whether legislative maps violate the law when there is evidence of racial vote dilution in redistricting or electoral methods. The Thornburg case created a test that requires examining the population of minority groups in a district and determining whether they are sufficiently large, geographically compact, and “politically cohesive,” whether their voting bloc is usually defeated by a majority (white) voting bloc, and whether in the totality of circumstances they have less opportunity than other citizens to elect their preferred candidates.

By officially recognizing the reality of electoral systems like multimember districts to dilute Black voting power, the Supreme Court provided an opportunity for minority voters to present evidence to transform discriminatory structures into functional remedial structures and thereby elect representatives who could be responsive to the needs of their communities. To this day, this has been a major civil rights achievement. Indeed, the more than 10,000 Black elected officials nationwide—along with many more Latinx, Native American, and Asian American and Pacific Islander elected officials—have been able to take office largely due to the transformative power of the Voting Rights Act, including Section Two.

i The senators on the brief were: Republicans Bob Dole, Charles Grassley, and Charles Mathias Jr.; and Democrats Edward Kennedy, Howard Metzenbaum, and Dennis DeConcini. The brief was also signed by two House Republicans (F. James Sensenbrenner and Hamilton Fish Jr.) and two House Democrats (Peter Rodino and Don Edwards).