Harvey Gantt: From Desegregating Clemson to Becoming Charlotte’s First Black Mayor

Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts and Culture in Charlotte, North Carolina. (Photo by Jeffrey Greenberg/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

In the winter of 1961, Harvey Gantt, a freshman studying architecture at Iowa State University, read a ranking of the country’s top 20 architecture schools while standing inside a building lobby on campus. He saw that Iowa State was lower on the list than Clemson College—a school in his home state of South Carolina.

Academically speaking, it would have made sense for Gantt to apply to Clemson’s prestigious architecture program as a high school senior. He had wanted to be an architect for years, his teachers commended his drawing abilities, and he was the salutatorian of his high school class. But he was also a Black man, and South Carolina had not integrated its higher education system—even though it had been seven years since the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling that segregated schools violated the U.S. Constitution. Gantt knew that it was his legal right to attend Clemson (which at the time was officially called Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina), so in early January 1961, he applied as a transfer student. It would take him 18 months, three applications, more than 10 rounds of correspondence, and a lawsuit to gain admittance. Gantt’s decision to challenge institutional racism led to the desegregation of higher education in South Carolina, and it also put him on the path to wage a Senate run nearly three decades later called “the ultimate struggle for the soul of the South.”

Pursuing a Quality Education

In a 2023 interview for the Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project, 80-year-old Gantt spoke of the importance that his father placed on education. Christopher Gantt, a naval shipyard worker, could not attend school after the eighth grade because he had no way of commuting more than 25 miles to the closest Black high school. He would not let that happen to his five children. He and his wife, Wilhelmina, raised their family on the west side of Charleston, South Carolina, in what their son called “a salt-of-the-earth, working-class neighborhood.” The Gantt family engaged in civil rights conversations around the dinner table, and the children accompanied their parents to speaking events at local Black churches sponsored by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In South Carolina’s segregated higher education system, Black undergraduates could either attend the state’s only Black public college, South Carolina State College for Negroes at Orangeburg, or, if State College did not offer their program of study, they could apply for funding through a state agency to subsidize their out-of-state-education. Harvey Gantt considered applying to a historically Black college, but his guidance counselor challenged him to try a predominantly white school. Gantt decided to apply to Iowa State because it had a good architecture program, and schools in the Midwest were generally more accepting of Black applicants. His biggest concern was about place, not race: He worried about leaving the South, “the place that I understood the soil, the people, the Gullah accent, Charleston.”

After a semester in Iowa, Gantt missed the Southern climate more than anything. His grades were good, but when he saw Clemson ranked above Iowa State on the list of architecture programs, he applied for a spring transfer. He identified his race as “N” in the demographic section of the application.

The rejection came within two weeks. The admissions office said the reason was financial: Because Gantt received financial aid from the state of South Carolina to attend an out-of-state school that year, Clemson said he was not eligible to attend an in-state school. Gantt asked to be considered for the following school year, beginning in September 1961. The Clemson registrar said his application would be placed with others that were pending. In April 1961, when Gantt asked for a progress report, the registrar said the school had not yet processed transfer applications. As Gantt finished his freshman year, he wrote again to request an update.

On June 8, six months after Gantt had first sent his application to Clemson, the registrar responded with a list of admission requirements that Gantt had not seen before. He learned he needed to submit Scholastic Aptitude Test scores, English and math college entrance exam scores, an official transcript, and a statement of achievement from Iowa State. Gantt wrote on June 17 that, having just learned about these requirements, he was working on them as quickly as possible. He further wrote, “Meanwhile, if there are any other requirements which I should meet in connection with my desire to enter Clemson, I shall appreciate your so advising me.”

Two months later, in August 1961, the registrar wrote that it would be impracticable for the school to process his application in time for matriculation on September 8. The registrar explained that his entrance exam scores had arrived too late, and he had never completed a personal interview. This was the first Gantt had heard about an interview requirement.

“It seemed like I was beating my head against a stone wall,” Gantt reflected in the 2023 interview.

On October 13, 1961, Clemson’s admissions department notified Gantt that it had canceled his incomplete application. They wrote that he could apply for another semester if he also completed a personal interview. By now, Gantt had an attorney—Matthew Perry, a South Carolina-based lawyer working with the national office of the Legal Defense Fund (LDF). The two had met before: When Gantt was a senior in high school, his NAACP Youth Council organized Charleston’s first sit-in to protest segregation at lunch counters, and Perry was one of several adults to advise the students as they prepared for the peaceful protest.

In response to the cancelation of his application in October 1961, Gantt asked Clemson admissions to either reconsider his application or send him a new one. They sent a new one that Gantt used to request admission for the spring or fall semester of 1962. He did not receive any response for five months. Then, at the end of Gantt’s second year at Iowa State, Clemson said his application was incomplete, without mentioning what was missing.

On June 13, 1962, Gantt arrived in person at the Clemson admissions office and asked for an interview. Officials refused because he had not yet submitted a transcript for the 1961-62 school year, which had just ended. Two weeks later, Gantt wired the registrar to say that Iowa State was forwarding his transcript, and he again asked for an interview. He was told that his application would be processed with others and instructed to wait for an interview date.

Gantt v. Clemson

On July 7, 1962, Perry filed a lawsuit on behalf of Gantt against Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of South Carolina. At the start of the lawsuit, Perry requested the Court enter an injunction ordering Clemson to stop denying Gantt admission solely because of his race. In its answer, Clemson argued that it had not accepted Gantt because he had failed to respond to requests for information in connection with his application. Five days before, on July 2, the dean of the School of Architecture had requested that Gantt schedule a personal interview and a portfolio review with the program. Gantt followed up, but when lawyers for Clemson learned of the lawsuit, they told his attorney that it would be “highly inappropriate” for his client to continue his application while the lawsuit was pending. The Court ultimately denied the injunction, and Gantt v. Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina went to trial in the District Court in November 1962.

By then, Gantt’s LDF team included Constance Baker Motley. Earlier that fall, she had represented James Meredith in his lawsuit against the University of Mississippi for denying him admission because of his race. One month before Gantt’s trial, on October 2, 1962, news networks across the country had televised images of Motley standing next to Meredith as he integrated Ole Miss. Resistance to integration sparked two days of violent protests in Mississippi that killed two people. Gantt described Motley as an “awe-inspiring” woman with a “commanding presence.” He marveled at how his LDF lawyers were “the most confident people I’d ever seen.” They told Gantt that they expected to lose the trial but win on appeal.

In District Court, Gantt’s attorneys argued that Clemson’s admissions team had handled his application differently from those of white transfer students who were already admitted to the school. “Every time Gantt’s application was complete, they came up with a previously unannounced new rule,” Motley said. Motley and the other LDF lawyers argued that Clemson was not in compliance with Brown’s desegregation mandate because the university had not changed its admissions policy for Black applicants since 1954, the Board of Trustees had never discussed admitting Black students, no Black student had ever successfully completed an application, and Clemson only actively recruited students from white high schools in South Carolina.

Clemson officials admitted “some deviation” in the handling of Gantt’s application. The registrar stated that while he would normally handle transfer applications, Admissions Director Kenneth Vickery had taken responsibility for Gantt’s paperwork.

In December, the District Judge sided with Clemson, saying Gantt had not earned admittance because he did not fully follow the school’s entrance requirements. The Court faulted Gantt for failing to interview and concluded that if he were “seriously interested in securing a good education in the field of architecture, he should have been glad to secure and consider the wise counsel of the Dean of Architecture of a great school like Clemson College.”

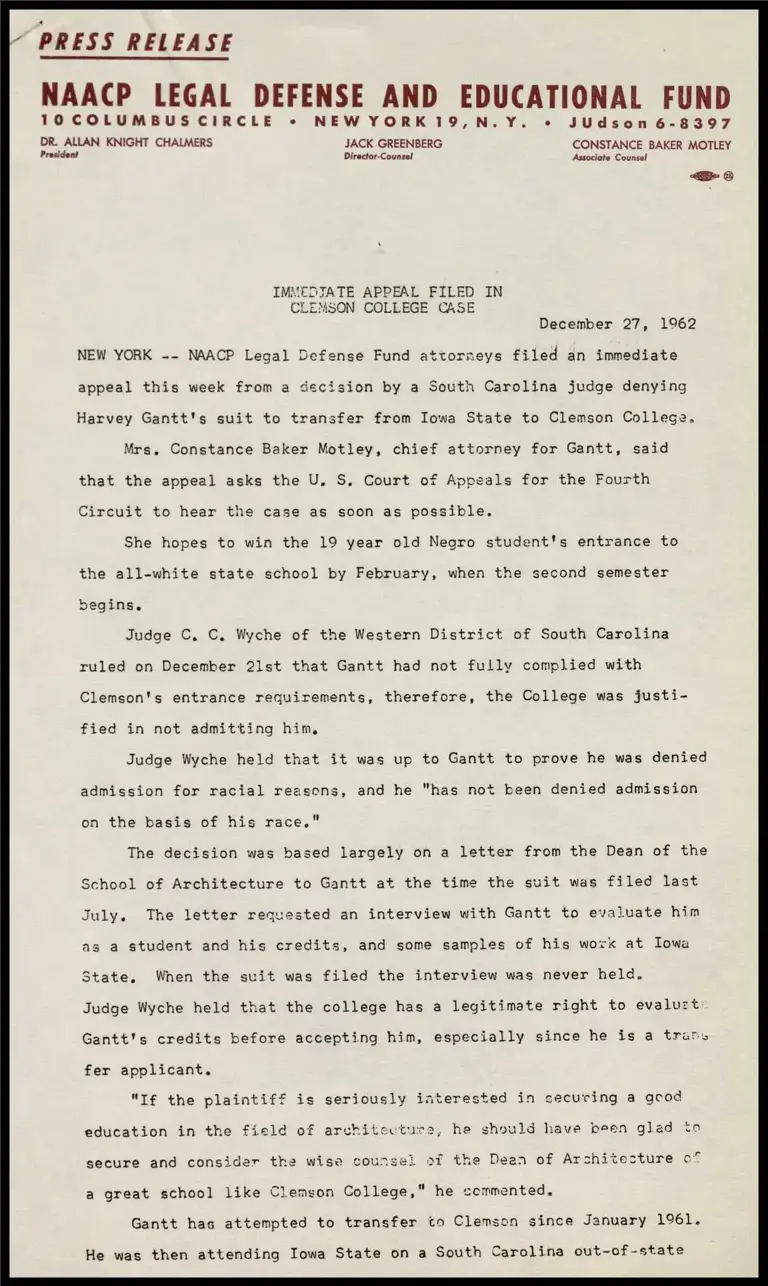

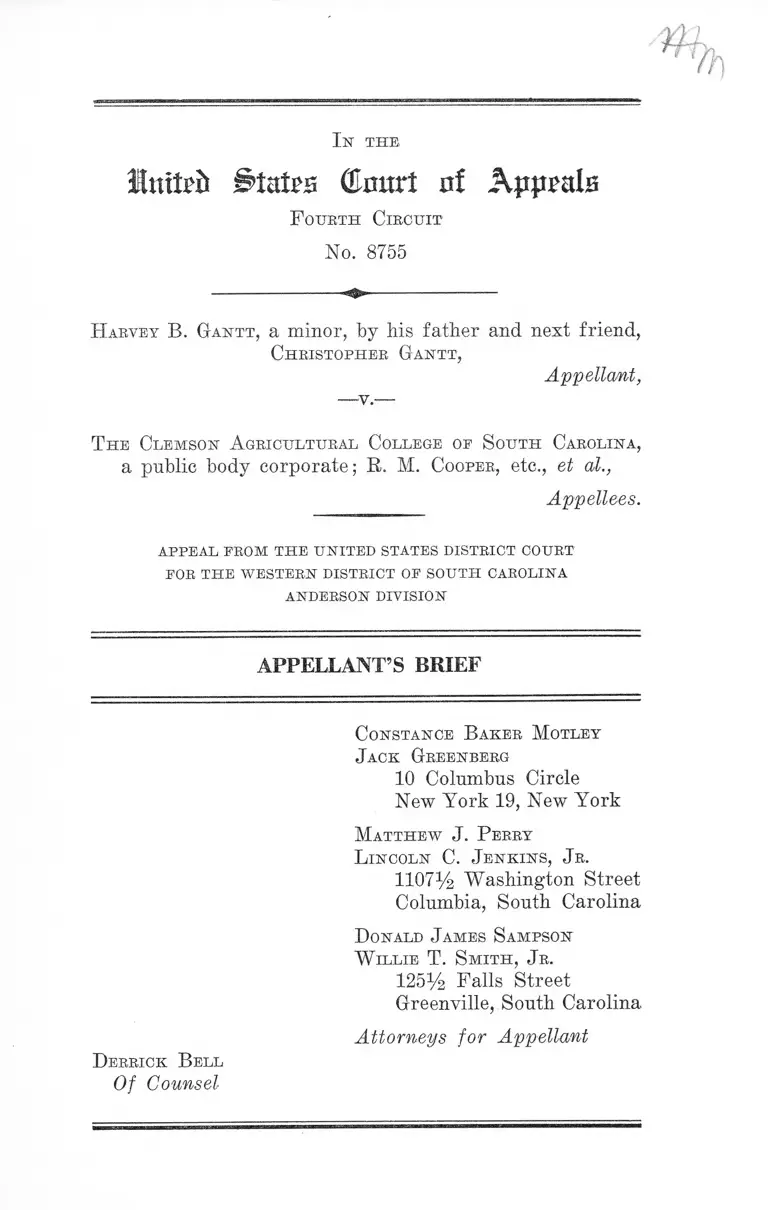

Immediate Appeal Filed in Clemson College Case

Gantt v. Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina Appellant's Brief

LDF filed an immediate appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. The brief stated that Clemson had “refused” pertinent application information after the lawsuit was filed, and that the burden was on Clemson to show its efforts to comply with federal law in admitting Black students. “Where a state school which has never admitted a Negro, refuses to admit or even pass on the application of one whom its officials admit is eminently qualified … the burden falls to the school to show by more than mere denials of racial discrimination that white students similarly situated are treated in like fashion.”

On January 16, 1963, a three-judge panel of the Fourth Circuit reversed the District Court’s decision, directing the District Court to issue an injunction against Clemson’s discriminatory admissions process and ordering Clemson to admit Gantt and all other qualified Black applicants.

Finally Heading to Clemson

By the end of January, Clemson officials had begun talking to Gantt and his legal team about his arrival on campus for the spring semester starting in February. Campus and state authorities did not want a repeat of the riots that had happened four months earlier in Oxford, Mississippi, with the desegregation of Ole Miss. Clemson President R.C. Edwards issued a statement that threatened expulsion to any student who acted “out of line” in protesting Gantt’s arrival on campus.

In a parting speech before the South Carolina legislature, Governor Ernest F. Hollings warned segregationists to cooperate with integration or risk another civil war. “We have all argued that the Supreme Court decision of May 1954 is not the law of the land, but everyone must agree it is the fact of the land,” Hollings said. “As determined as we are, we of today must realize the lesson of 100 years ago and move on for the good of South Carolina and our United States.”

On the morning of February 2, 1963, Gantt began his trip to Clemson to start his junior year of college. Perry described him in the days leading up to this journey as “a cool young man, the calmest of us all.” The day began with two prayers—one at the Gantt home in west Charleston, and the second at Perry’s office in Columbia, South Carolina. The lawyer drove most of the way in his Buick with Gantt, along with Gantt’s father and minister. Just outside of Clemson, in Greenville, South Carolina, Perry dropped off Christopher Gantt and the minister and met with a group of highway patrolmen on detail to take Harvey Gantt to campus. As they made their way to Clemson, there were more officers lining the entrances to check incoming cars for weapons. After the court decision, a group of leading white local businessmen had worked to ensure an orderly transition, but nobody could be sure what Gantt would face on campus—especially following so closely the violence that had met Meredith’s arrival at Ole Miss.

Two hundred students gathered to watch Gantt register for classes. Only two protesters were ultimately ejected from the school grounds. The largest commotion came from the more than 150 local and national reporters who bombarded Gantt with so many questions during his first hours on campus that he stopped answering them.

After the first day, Gantt settled into a quiet college life. When he crossed the courtyard alone, he would occasionally hear someone yell, “Nigger, go home!” from a high-rise dormitory, but he ignored the taunting. He socialized with some of his architecture classmates, but most of the time he ate alone. When he was not in class or the dining hall, he studied in his single room in a dormitory usually reserved for graduate and international students. His only regular partner for mealtimes was Lucinda Brawley, Clemson’s second Black student. The two would later marry.

NAACP Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins called the peaceful desegregation process in South Carolina “a significant turning point in the current integration struggle.” As Clemson opened its doors to Black students, it expanded its academic courses and programs. In 1964, one year after Gantt’s admission, the school became a fully accredited university and changed its name from Clemson College to Clemson University. Gradually, more Black students followed in Gantt’s footsteps. As of 1973, 179 of Clemson’s 8,500 students were Black.

In the decade after his graduation, Gantt achieved a graduate degree in urban planning from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and returned to Clemson as a visiting professor to teach a class on urban design.

Running for Office

In 1990, nearly three decades after integrating Clemson, Gantt would be a main figure in another story that tested civil rights progress in the South when he ran against incumbent U.S. Senator Jesse Helms, a right-wing politician who was openly hostile to civil rights. Gantt would use the lessons he learned from desegregating Clemson in his campaign against Helms, saying, “What I think the experience of my earlier life said, to me, was I need not be intimidated by what he represented.”

Soon after Gantt finished his education, he and Brawley settled in Charlotte, North Carolina, where they would raise four children. He co-founded Gantt Huberman Architects, a firm that prioritized building designs that improved neighborhoods.

Gantt’s expertise in urban design served as a natural transition into public service. “It was architecture and city planning that got me involved in politics,” he reflected in the 2023 interview.

In 1974, Gantt was asked to fill the City Council seat vacated by Fred Alexander, recently elected to the North Carolina Senate. Gantt served as a councilmember until 1983. That year, he became Charlotte’s first Black mayor, earning approximately 41% of the vote in predominantly white neighborhoods, one of the highest margins recorded by a Black mayoral candidate. Gantt served as mayor for two terms.

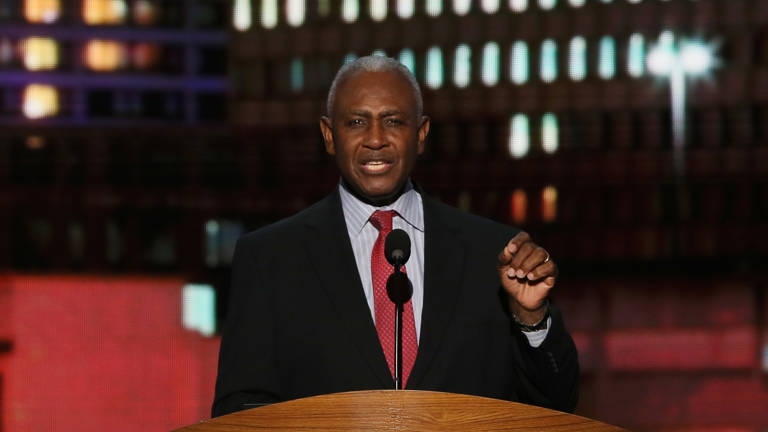

Harvey Gantt speaks at the Democratic National Convention on September 6, 2012, in Charlotte, North Carolina. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

In 1990, he decided to challenge Helms, a three-term Republican incumbent, for his U.S. Senate seat. Gantt and his team knew that it would not be easy to defeat Helms, a masterful fundraiser and polarizing force. But if successful, Gantt would become the first Black senator from the South. Gantt recalled thinking, “We’ll run, if for no other reason than to present an alternative platform to the citizens of North Carolina.”

The New York Times commented on the irony of this pioneering Senate campaign in a state with “one of the nation’s highest reported levels of hate crimes and Ku Klux Klan activity.” The paper described the race between Gantt (“a symbol of the increasingly diverse and urban character of the region”) and Helms (“a contentious conservative who as much as anyone symbolizes the South’s rural traditions”) as “the ultimate struggle for the soul of the South.”

Bolstered by a growing Black voter turnout, the Gantt campaign was hopeful that it could also harness the youth vote and a majority of white working-class voters. Helms had won the popular vote in three Senate campaigns, but he did not connect with a large percentage of moderate North Carolina residents. He drew much of his financial support from elderly, out-of-state, right-wing conservatives who appreciated his open antagonism toward civil rights, international aid, and LGBTQ rights.

A former journalist and media consultant to segregationist politicians, Helms was known for his media savvy. At a Democratic rally early in the race, Gantt warned his supporters to rise above any derogatory campaigning that Helms would use, saying, “I think it’s very important that we not allow this campaign to drift off into those hot-button, emotional issues that I call Jesse Helms’ pasture.”

Gantt repeatedly offered to debate Helms, but the incumbent refused. Weeks before the election, Helms’ team released a racist television advertisement that implied Gantt would prioritize Black job security over white employment rates. The scare tactics worked, as polls later showed that Helms drew thousands of undecided white voters to his cause. Meanwhile, the North Carolina Republican Committee sponsored a direct mail campaign that sent 150,000 postcards to predominantly minority precincts. The postcards lied to voters, warning them that if they voted after recently moving, they could be arrested for voter fraud. This tactic persuaded many Black voters to stay away from poll sites on election day.

Although Gantt won 35% of the white vote, he lost the election by an overall margin of 47% to 53%. In 1996, he again ran against Helms, but lost by about the same margin.

“Still Fighting the Same Battles”

In the 2023 interview, Gantt said that through tactics like restricting the time and place of elections and supporting voter identification laws, officials today play “the same game” as Helms and a host of others did decades ago. “It is amazing to me that we’re still fighting the same battles,” he said. He remembered having this conversation with his good friend and former LDF Director-Counsel Julius Chambers. Discussing their life experiences, the two would marvel over how “change is so hard to come by.”

Gantt told reporters in 1991 that he was nonetheless proud of his campaign against Helms, saying, “There’s almost nothing I would change about 1990. I liked our issues. I liked the way we ran. … You’ve got to just keep hoping that people will continue to grow.”

Decades later, Gantt said he works to help younger generations grow by spending as much time as he can with his nine grandchildren, and by talking with young people. When he meets with college students, he tries his best to listen to them and to encourage them to step up, lead, and move forward.

“Like my dad winked at me and said, ‘Keep going, boy.’”