Major v. Treen: Combatting Black Voter Dilution in Louisiana

For generations, Black residents of Louisiana watched as a white voting bloc diluted the strength of their votes. To remedy the situation, in November 1981 the state legislature approved a plan to realign Louisiana’s congressional districts to create the state’s first majority-Black district in the New Orleans metropolitan area. However, Louisiana Governor Dave Treen threatened to veto it. Even though 1980 census data supported redistricting and both houses of the state legislature had approved it, Treen—a former official in the segregationist States’ Rights Party—had publicly expressed his belief that any use of race as a factor in districting schemes was unlawful. His threat to block the majority-Black district intimidated legislators into withdrawing their support, and Treen soon signed into law a bill that maintained white majorities in each of Louisiana’s eight malapportioned congressional districts.

Major v. Treen Memorandum Opinion

On behalf of five Black voters and the broader Black electorate in Louisiana, the Legal Defense Fund (LDF) sued the state for diluting the Black vote in violation of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution and Section Two of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, among other statutory claims. The 1983 case Major v. Treen centered on whether a law separating a “highly concentrated” Black population in the New Orleans metropolitan area into different districts, rather than creating one majority-Black district, deprived Black voters of the right to effectively participate in the electoral process.

Excerpt of LDF 1982-83 Annual Report

During the summer of 1981, as Louisiana’s legislature prepared to apportion the state into congressional districts, the U.S. Congress was debating amendments to the Voting Rights Act of 1965—a landmark law that prohibited race-based restrictions on voting. Civil rights advocates wanted, among other changes, an extension of Section Five of the act, which required jurisdictions with histories of discriminatory voting practices to “preclear” any voting changes with the Department of Justice (DOJ) or a federal court before they went into effect by showing the changes would not harm minority voters.

Louisiana had such a history of disenfranchising Black voters. Between 1868 and 1896, after the 14th and 15th Amendments granted citizenship to Black people and gave Black men the right to vote, a number of Black legislators held state office in Louisiana. This changed in the late 1890s, when legislators added a grandfather clause for voter registration to the state constitution and required applicants to meet new educational and property qualifications. These changes reduced the state’s registered Black voters from 135,000 in 1896 to less than 1,000 in 1907. Disenfranchisement continued into the 20th century as officials required poll taxes and citizenship tests. Louisiana also held all-white Democratic primaries, a practice the Supreme Court later deemed unconstitutional in Smith v. Allwright, a 1944 case argued by LDF founder Thurgood Marshall. Therefore, regardless of how the Louisiana state government redrew its congressional districts in 1981, lawyers in the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division would have to review the changes before the state implemented them.

Shifting Demographics

The U.S. Constitution requires that states undergo a process of redistricting every 10 years to make sure that districts are aligned with census data. In 1980, as Louisiana was going through this process, legislators saw a marked demographic change in Orleans Parish, one of five parishes in the New Orleans metropolitan area and home to the city of New Orleans. Prior to 1980, most voters in Districts One and Two lived in Orleans Parish. Census data, however, showed a decline in the population of Orleans Parish. While the parish’s overall population declined, the Black population of the city increased from 45% in 1970 to 55% in 1980. Even so, less than 15% of New Orleans’ politicians were Black.

The Louisiana Legislative Black Caucus argued that the state should create one majority-Black district within Orleans Parish that maintained the cohesiveness of the metropolitan Black community. Should the legislature keep the majority-Black population of Orleans Parish divided between Districts One and Two, it would dilute the Black vote because white voters formed racial blocs that elected far more white than Black officials. Several white officials agreed with this reasoning because the facts were clear: At no time in the 20th century had a Black person from Louisiana won election to Congress or to statewide office.

Showdown with the Governor

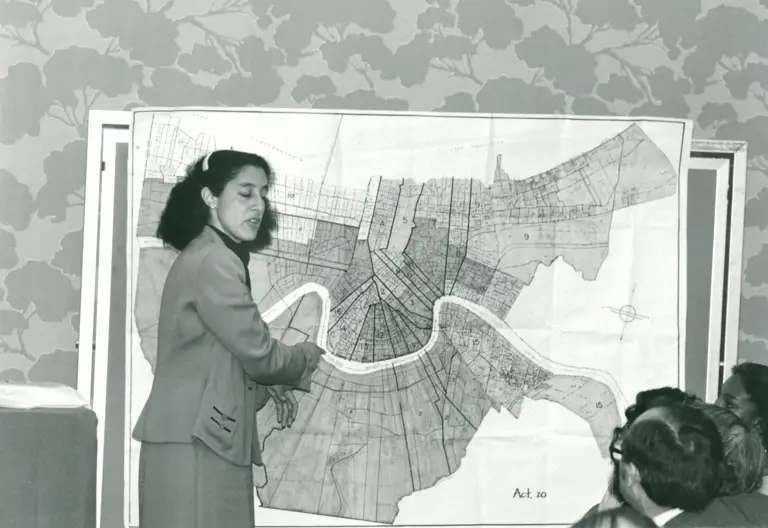

In October 1981, ad hoc reapportionment committees in both houses of Louisiana’s legislature were charged with generating multiple redistricting options that realigned the state’s congressional districts with the census data. The state Senate research staff generated more than 50 different redistricting possibilities. State Senator Samuel Nunez Jr. sponsored the most popular redistricting plan. The Nunez Plan incorporated the natural geographic barrier of the Mississippi River and placed the boundaries of District Two almost completely within Orleans Parish, turning it into a majority-Black district. After passing the Senate, the Nunez Plan moved to the House, where representatives voted 61 to 38 to adopt a bill incorporating the plan.

However, Treen denounced the representatives’ redistricting plan, threatening to veto the bill if it passed. Never in Louisiana history had a legislature overruled a gubernatorial veto. Legislators began withdrawing their support. On November 9, 1981, Treen unveiled a “Reconciliation Plan” in which all eight congressional districts had white voting majorities. That afternoon, the Louisiana House reversed its stance on the Nunez Plan and voted 79 to 22 in favor of the Reconciliation Plan, but the Louisiana Senate rejected it.

In need of a compromise, the Senate president summoned “interested” legislators to attend a private meeting in the sub-basement of the State Capitol building. Lawmakers discussed the governor’s redistricting agenda, including his goal to incorporate more white suburban voters into District One to help the political fortunes of an ally. They realized that if the legislature adopted a majority-Black plan for District Two, they could not satisfy the governor and other politicians who had their own competing interests. This underground meeting produced a compromise plan that Treen approved. On November 19, he signed into law Act 20 of the First Extraordinary Session of 1981 of the Louisiana Legislature.

The Gerryduck

Act 20 used a “jagged line” that “cracked” Black communities while preserving the unity of white neighborhoods. The oddly divided territory limited the political power of the Black electorate and resulted in a boundary for District One with more than 30 jagged sides—meaning the district was not “compact,” which is a factor courts consider when analyzing a Voting Rights Act claim. After critics said that the “gerrymandered” lines for District Two resembled an outline of Donald Duck, reporters gave Act 20 the nickname “Gerryduck.”

Lani Guinier with a map of the "Gerryduck" district

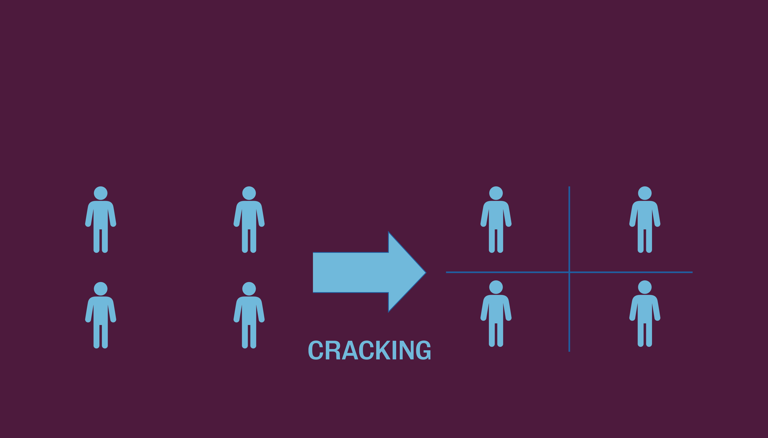

"Cracking”

refers to splitting communities of color into different districts to prevent them from exercising greater political power.

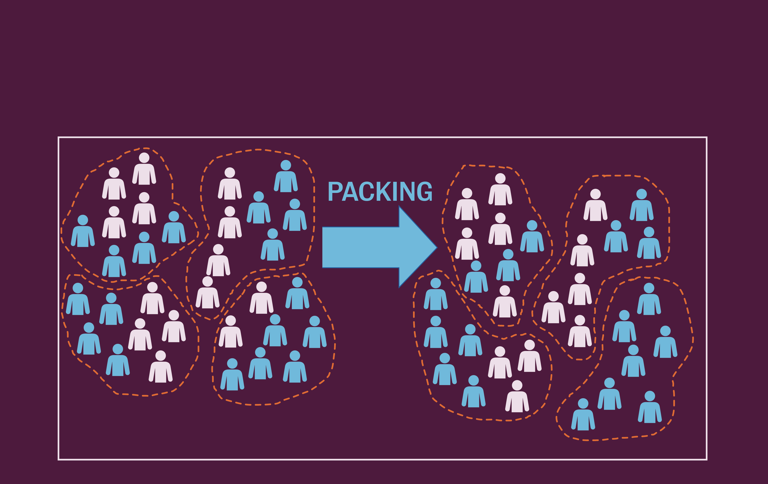

“Packing”

refers to placing people of color into the same district, in larger numbers than necessary to elect candidates of their choice, to prevent them from exercising greater political power in surrounding districts.

Source: Thurgood Marshall Institute, adapted from Brennan Center Gerrymandering Explainer (Julia Kirschenbaum & Michael Li, updated June 9, 2023).

“The map clearly and unquestionably demonstrates efforts by the state of Louisiana … to stop [B]lack participation in state government,” Barbara Major, Chairwoman of the grassroots organization Survival Coalition, told the Abbeville Meridional newspaper. “If they wish to play with a puzzle, we’ll send them a puzzle of Donald Duck to play with rather than playing with Orleans Parish.”

Pursuant to Section Five of the Voting Rights Act, the state sent Act 20 to the DOJ for preclearance approval. Treen said he was confident the DOJ would approve it.

On behalf of Major and four other Black voters representing the broader Black electorate of Louisiana, LDF sued the state, challenging Act 20 on statutory and constitutional grounds.

“The actions of the governor had both the effect and the intent of diluting [B]lack voting strength in Louisiana,” William Quigley, LDF affiliate local counsel, told the press.

A team of lawyers in the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division agreed. Gerald W. Jones, head of the voting rights section, drafted a letter to Treen on February 2, 1982, asking why the governor had threatened to veto a majority-Black district and what he had meant by his prior statement that “carving out a mostly [B]lack congressional district does not serve the interest of [B]lack people. ” He also asked on what basis Treen thought his plan would enhance the ability of Black voters to influence elections.

The same day that Louisiana officials received this letter, they mailed it to U.S. Assistant Attorney General William Bradford Reynolds in Washington, D.C. Reynolds’ response reflected the Reagan administration’s ambivalence about enforcing the Voting Rights Act. After reviewing the letter, Reynolds told Jones and his team of lawyers that the references to Treen were “unnecessarily rude.” He had them rewrite their question about the governor’s statement to exclude any mention of the governor. LDF later called this move “a most unusual gesture of concern for the feelings of the governor of Louisiana.”

Jones and other career voting rights experts (who were not political appointees) in the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division sent Reynolds a memorandum advising him to reject Act 20. Reynolds did not take their advice: On June 18, 1982, he approved Louisiana’s plan as nondiscriminatory.

Also in June, Congress amended and extended the Voting Rights Act. The strengthened act made it easier to argue discriminatory voting procedures under Section Two. Whereas before, plaintiffs needed to show evidence of “discriminatory intent” when contesting a voting practice, they now only needed to show evidence of a “discriminatory effect.”

Backdating a Memo

During the last week of June 1982, LDF filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the DOJ asking for a copy of the memorandum written by the government attorneys who expressed concerns about Louisiana’s bill. Instead of providing the requested memo, the DOJ gave LDF a different memo dated June 18, 1982, in which Reynolds explained his approval of Louisiana’s plan. Defending Treen’s intentions, Reynolds said that Act 20 was “not racially discriminatory in either purpose or effect.” He wrote that the legislature had rejected an earlier proposal to create a district with a larger percentage of Black voters “for political—not racial—reasons.”

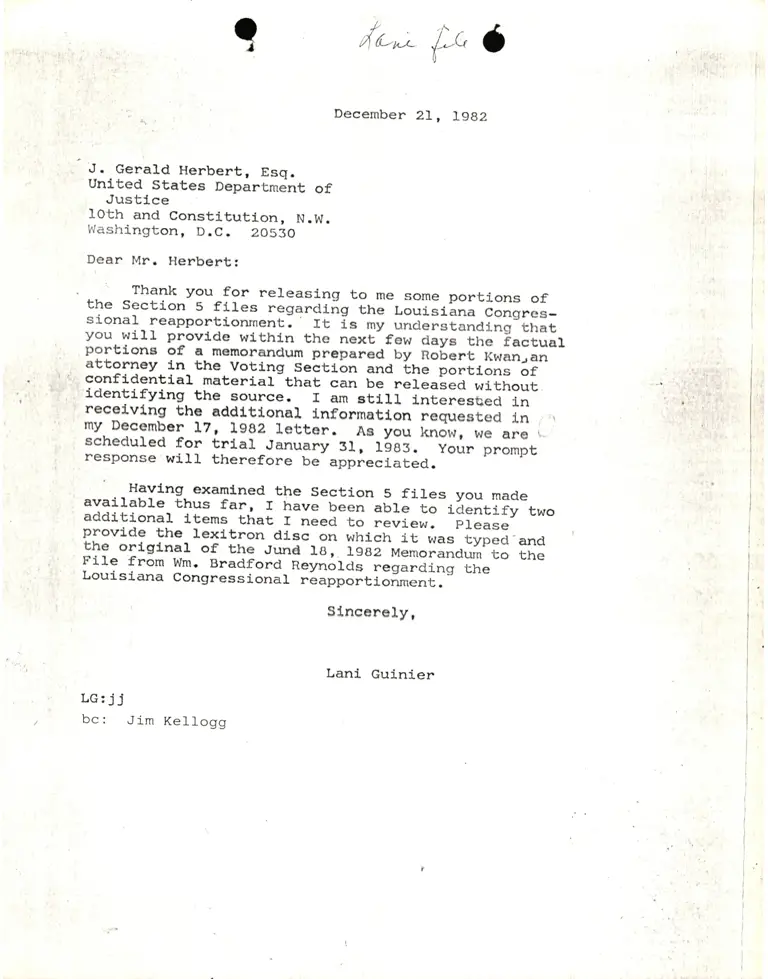

LDF attorneys, which included voting rights expert Lani Guinier, noticed that someone had typed the word “June” over “July.” They also saw a routing and transmittal slip connected to the memo on which Jones of the voting rights section had made a note on July 19 stating, “Please make sure this gets into the Section 5 file. It’s dated 6-18-82 but I received it today.” The LDF team assumed that the DOJ had backdated the memo to sidestep their FOIA request for the government attorneys’ memo and to justify Reynolds’ overruling the recommendation of his staff experts that the plan was objectionable. Months later, the DOJ admitted changing the date, but Reynolds claimed there was “nothing nefarious or sinister” about the date change.

LDF attorneys knew the June 18 date benefited Treen. After Congress voted to strengthen the Voting Rights Act with bipartisan support, President Ronald Reagan signed the amendments into law on June 29, 1982. If Reynolds had approved Louisiana’s law at any time after that date, Treen would have needed to resubmit Act 20 for preclearance under the stronger legislation. By backdating the memo, Reynolds could say that Act 20 was evaluated under the earlier version of the Voting Rights Act. Guinier later discovered that Reynolds had written the statement in mid-July after returning from a trip to Louisiana, where he had dined and traveled at the state’s expense. LDF also used a FOIA request to obtain Reynolds’ phone records, which showed that Reynolds had spoken to Treen at least 15 times between July 1981 and June 1982, when the department approved the plan. The DOJ denied what LDF called a “highly irregular” review.

The Fight Moves to the Courts

On September 11, 1982, under the redistricting plan of Act 20, U.S. Rep. Robert Livingston Jr.—the political ally whom Treen had worried might not get reelected in a majority-Black district—won his District One primary election in a landslide, with 86% of the vote.

Four months later, LDF filed papers in federal district court asking for an immediate injunction blocking further use of the new voting districts. Arguing that Reynolds had precleared Act 20 because of “personal and political considerations unrelated to the purposes of the statute he was responsible for enforcing,” LDF asked the court to remand the DOJ’s preclearance because it was “the result of an unreliable and untrustworthy decision-making process.”

Letter from Lani Guinier to J. Gerald Herbert, DOJ

Major v. Treen went to trial before a special three-judge panel in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana in March 1983. LDF concentrated its strategy on proving how racial bloc voting limited Black electoral participation. Experts from The University of New Orleans testified that racial bloc voting in majority-white congressional districts kept Black politicians from office. Political science professor Dr. Richard Engstrom showed evidence that Black and white voters cast their votes along racial lines, and history professor Dr. Ralph Cassimere said that when Black politicians had gained electoral momentum in recent years, white voters then rallied in increasing numbers to vote for white candidates. This behavior resulted in racially polarized voting, the professors testified.

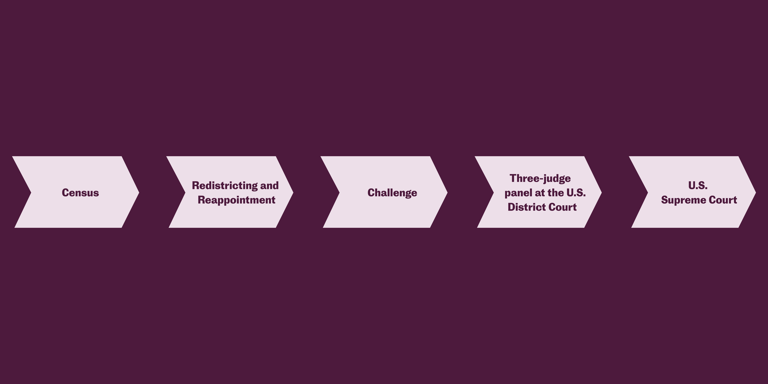

Procedural History of Voting Rights Cases

Chief Judge Henry Politz of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit heard final arguments alongside federal District Court Judges Fred Cassibry and Robert F. Collins on June 29, 1983. LDF attorney Guinier asked that the Court throw out Act 20 and create a majority-Black district in Orleans Parish from which a Black person could be elected the following year. Pointing out that both majority-white districts had white representatives (Republican Rep. Livingston represented District One, and Democratic Rep. Lindy Boggs represented District Two), Guinier asked the Court to act expeditiously so that Black candidates would have ample time to fundraise and campaign for the next election cycle.

Representing Treen and the state of Louisiana, attorney Martin Feldman (whom Reagan had recently nominated to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana) denied that the legislature had discriminatory intent in its redistricting. He repeated what Treen had been saying for over a year: that Black voters in Orleans Parish had a congressional advantage by being able to vote in two different districts, as opposed to being compressed into one.

Judge Politz noted during oral arguments that since 1843, the population of New Orleans had been divided between two congressional districts. “Why does a division all of a sudden become illegal and unconstitutional?” he asked.

The Associated Press summarized Guinier’s response during the oral arguments that such a division was illegal because “it perpetuates a longstanding state policy of racial discrimination and does it in such a way as to render the city’s [B]lacks politically impotent.” She argued that throughout the 20th century, most of the Black voter constituency had not been represented because such districting diluted their votes.

Feldman responded that despite having a majority-white voting population, New Orleans had elected a Black mayor twice, three Black judges, a Black sheriff, a Black clerk of court, and two Black councilmembers. Guinier countered that even so, less than 7% of state elected officials and less than 15% of municipal elected officials were Black.

“Do white people have the constitutional obligation to create a majority-Black district?” Feldman asked.

“No,” Judge Cassibry replied, “but they have the obligation not to prevent it.”

On September 23, 1983, the three-judge panel decided in favor of the Black voters and ordered the state to redraw district boundaries by January 31, 1984, prior to the elections that year. If the state did not, the panel of judges would reconvene on February 6, 1984 to do it for them.

In his opinion, Judge Politz wrote that the state legislature had created the congressional district boundaries of Orleans Parish to limit Black voting strength after the 1980 census, violating the federal Voting Rights Act. He called Act 20 “an electoral scheme which splinters a geographically concentrated [B]lack populace within a racially polarized parish, thus minimizing the [B]lack citizenry’s electoral participation.” He said the district boundaries that the governor had signed into law were “clearly racial in character.”

An Impactful Victory

Jim Kellogg, a New Orleans attorney working with LDF, told the press, “This is the first time in U.S. history that a plan has been thrown out by a district court when it has been approved by the Justice Department beforehand. It’s a big win.” He explained that Treen now had two options: call a special legislative session to realign the boundaries of District One and District Two to create a majority-Black voting district, or appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Within hours of the decision, Treen chose not to appeal to the Supreme Court. The governor immediately called for a special legislative session.

“It should be emphasized that at no time did I oppose the idea of a congressional district with a [B]lack majority,” Treen said. “I am confident a congressional redistricting plan can be devised to bring about a majority-[B]lack district without seriously disrupting the First District.”

The following month, after the state legislature created Louisiana’s first majority-Black district in District Two, Treen lost his reelection campaign, earning only 36% of the vote.

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to James Kellogg, William Quigley, and Steven Scheckman re: Major v. Treen

The New York Times Editorial Board wrote that it hoped the Major v. Treen ruling would hold the DOJ accountable by serving “as a call for more vigilance by those who enforce the civil rights laws.” In a pointed criticism of Reynolds, they further wrote, “The higher-ups in the department ought at least to learn how to recognize a gerryduck. Voters should not have to go to court to make the Justice Department do its job.”

Months after Louisiana’s special legislative session met to create a majority-Black district in Orleans Parish, the Rev. Jesse Jackson won the Louisiana state primary in his bid for the 1984 Democratic presidential nomination. The victory made Jackson the first Black man to win a presidential primary for a major political party. The Washington Post noted that Jackson’s biggest plurality “came from the newly created, predominantly [B]lack Second Congressional District in New Orleans.” In 1991, District Two voters elected William Jennings Jefferson to the U.S. House of Representatives, making him Louisiana’s first Black member of Congress in more than 100 years.